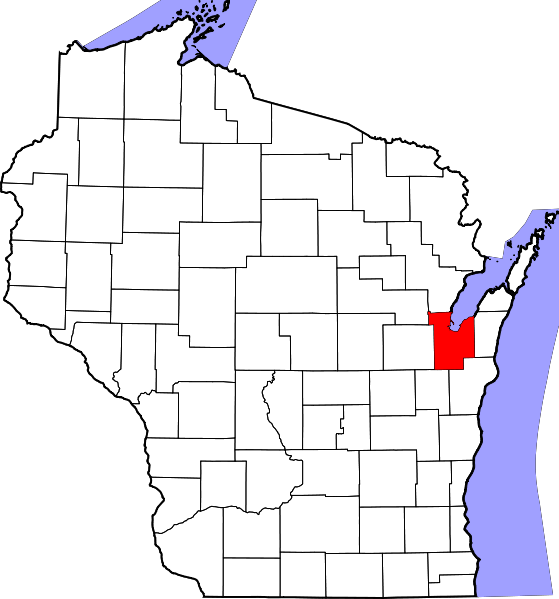

SPECIAL TO BROWN COUNTY, WISCONSIN: Towns of Morrison, Holland, Wrightswood, and Glenmore

SPECIAL TO BROWN COUNTY, WISCONSIN: Towns of Morrison, Holland, Wrightswood, and Glenmore

Brown County Citizens for Responsible Wind Energy [BCCRWE] is a grassroots organization made up of local residents who are concerned about the impacts of Invenergy's Ledge Wind Project proposed for the Towns of Morrison, Holland, Wrightstown and Glenmore.

If you'd like to learn the latest news about the project, or meet some of your concerned neighbors,

Visit the BCCRWE website by CLICKING HERE

The Public Service Commission is now taking public comment on the project, and maintains a docket containing information about the project.

Visit the docket by CLICKING HERE and entering the case number: 9554-CE-100

Leave a comment on the project on the docket by CLICKING HERE

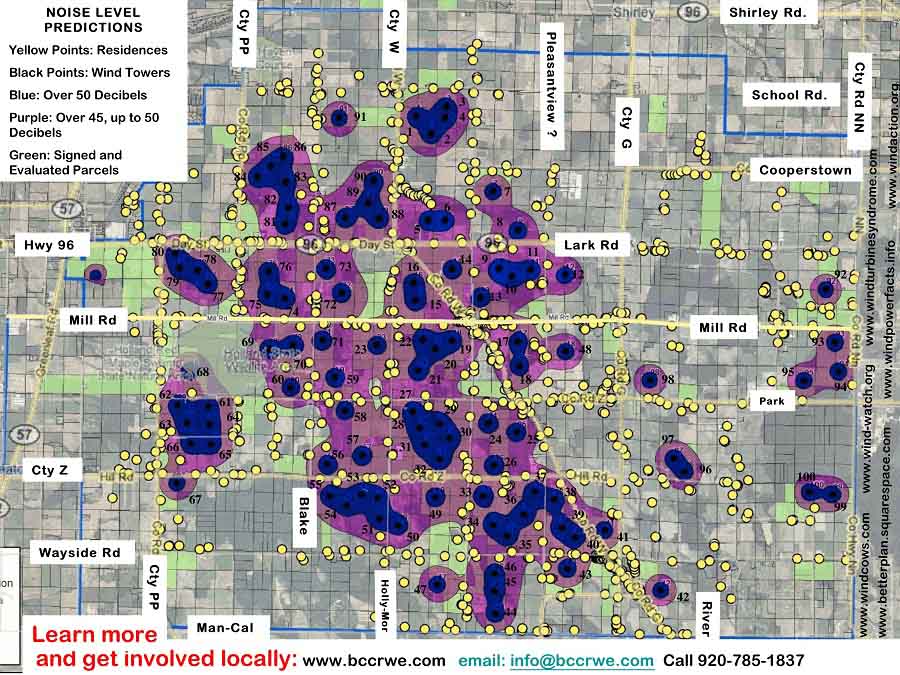

Below is a map showing the noise level predicted for residents in the project. The yellow dots are homes. THe black dots are wind turbine locations. The blue areas indicate predicted noise levels above 50 dbA. The purple areas indicate noise levels of 50dbA.

Unfortunately noise from turbines that are 40 stories tall doesn't stop at the boundries drawn on this map. The setback proposed for this project is 1000 feet from non participating homes.

The World Health Organization recommends night time noise limits of 35dbA or below for healthful sleep. Loss of sustained sleep because of turbine noise is the most common complaint from Wisconsin wind farm residents.

Better Plan, Wisconsin has been following the story of our eastern neighbors on the Island of Vinalhaven who are finding it impossible to live with the noise of the turbines they welcomed with open arms.

Unfortunately it's a story that is being told where ever wind turbines are placed too close to people's homes, including our own state of Wisconsin.

WIND POWER OVERPOWERS ITS NEIGHBORS

Kennebec Journal & Morning Sentinel,

morningsentinel.mainetoday.com

By Tux Turkel

24 January 2010

VINALHAVEN — Cheryl Lindgren was excited when the three wind turbines down the road began turning in November, but within days her excitement turned to disbelief. The sound at her house, a half-mile or so away, wasn’t what she had expected. As she sat reading in her quiet living room, she could detect a repetitive “whump, whump” coming from outside.

“I can feel this sound,” she recalled thinking. “It’s going right through me. I thought, ‘Is this what’s it’s going to be like for the rest of my life?’ ”

Dedicated two months ago with great fanfare, the Fox Islands Wind Project is producing plenty of power, but also a sense of shock among some neighbors.

They say the noise, which varies with wind speed and direction, ranges from mildly annoying to so intrusive that it disturbs their sleep.

They also say they lament losing the subtle quiet they cherished in living in the middle of Penobscot Bay — the muffled crash of surf on the ledges and the whisper of falling snow.

The folks living around North Haven Road aren’t anti-wind activists. Lindgren and her husband, Art, supported the project as members of the local electric co-op.

Now the Lindgrens are discovering what residents in other communities, including Mars Hill and Freedom, have learned: When large wind turbines are erected, some people living near them will find their lives disrupted.

That wasn’t supposed to happen here. Co-op members on Vinalhaven and in neighboring North Haven endorsed the $15 million project as a way to hold down high electric rates and maintain a sustainable community. The developer, backed by the Rockland-based Island Institute, saw it as a model for other offshore towns.

In the wake of the complaints, the developer is taking extraordinary steps to try to lessen the effect. Several modest fixes are under way, and bigger ones are being considered, including some that could sacrifice energy output.

However, the Vinalhaven experience also is being seen as a cautionary tale. Upon invitation, Art Lindgren and other neighbors have spoken at meetings in mainland towns where new wind farms are being proposed.

Meanwhile, wind power opponents are attempting to change the state noise standards to affect which projects are permitted. All this may complicate Maine’s efforts to use its renewable resources to become more energy independent and create an industry around wind power.

In no-man’s land

The Vinalhaven project consists of three 1.5-megawatt turbines. They are a massive presence on a high point of land at the island’s northwest corner, a 10-minute drive from the ferry terminal. Each unit stands 388 feet high, from ground to blade tip.

The ribbon-cutting in November drew more than 400 people and attracted national media attention. Schoolchildren passed out pinwheels. Visiting dignitaries applauded New England’s largest coastal wind project.

The 15 or so property owners within a half-mile of the turbines watched with special interest.

To get state approval for a wind farm, developers must keep sound levels offsite below 45 decibels, less than the background noise in an average household. Fox Islands Wind purchased a home and two vacant properties that were adjacent to the towers. A fourth owner turned down a buyout offer, seeking more money.

However, the Lindgrens and others suddenly found themselves in no-man’s land: Their homes are technically outside the noise zone, but their ears say otherwise.

The Lindgrens built their home 10 years ago next to Seal Cove. They have goats and ducks and heat with wood. After much travel and a career in software development, the couple looked forward to a peaceful retirement. Instead, they now spend much of their time measuring sound levels, comparing notes with neighbors and learning the details of wind power.

Cheryl Lindgren values quiet. On a recent stormy evening, she recounted when she first came here and stood at the shoreline in the snow.

“All I could hear was the sound of snowflakes falling on my jacket,” she said. “That’s not going to happen again.”

‘Unsettling and unpleasant’

On this evening, the Lindgrens were having cake and coffee with three other neighbors who are troubled by turbine noise. They’ve already developed a vocabulary to describe the shifting sounds.

One sound is like sneakers going around in a dryer. Another mimics an industrial motor. There’s a ripping and pulsing of blades cutting through the air, and the rotational “whump, whump, whump” sound.

Another common sound, which was audible on this evening from the Lindgrens’ front porch, resembles a jet plane that’s preparing to land, but never does. That sound was produced by two turbines spinning in a moderate northeast blow that followed the snowstorm. The third turbine was offline for repairs.

“That’s fairly standard,” Cheryl Lindgren said, “and that’s just with two turbines. Factor in the third and it’s unsettling and unpleasant.”

For Ethan Hall, the sound is more than unpleasant.

Hall is a young carpenter who’s building a small homestead on a height of land past the Lindgrens, roughly 3,000 feet from the nearest turbine. The noise was so annoying on some nights, Hall said, that he couldn’t sleep in the passive-solar, straw-bale structure. Now he’s house-sitting in town.

“I find it maddening,” he said. “It’s a rhythmic, pulsing sound that’s impossible to ignore.”

Art Farnham is trying to ignore the noise, although he can clearly hear it inside his mobile home. A lobsterman who lives 1,300 feet from a turbine, Farnham turned down an offer to buy his 6-acre property. He continues working on a new home and shop that will have a turbine almost in its backyard.

“I think they should shut them down,” he said. “We were here before they were.”

Between Hall and the Lindgrens is the home of David and Sally Wylie. They built in the once-quiet cove, and like their neighbors, did much of the work themselves.

“This has been our dream, our life,” Sally Wylie said from their winter home in Rockland.

Set into the snow on the Wylies’ lawn is a tripod and meter that Fox Islands Wind is using to measure sound levels, but that’s little comfort to Sally Wylie, who believes the computer modeling used to approve the project is wrong. The only solution now, she said, is to turn down the turbines to a point that they are quieter, but still produce an acceptable amount of power.

“It really boils down to what the community is going to accept,” she said.

Reducing sound cuts power

The task of trying to find a remedy for the noise complaints has fallen to George Baker, chief executive officer of Fox Islands Wind LLC.

Baker has spent the past two months taking sound measurements, studying computer models and talking to neighbors and the turbine manufacturer, General Electric. He slept one windy night at a vacant house 1,110 feet from two turbines, to experience the sound. He said he could hear the turbines but they weren’t particularly loud and didn’t prevent him from sleeping.

Baker recently e-mailed neighbors to outline his initial plans. Workers will make small modifications to the equipment. They’ll change the turbines’ gearbox ratio, for instance, and close air vents in the nacelles, the housing that covers components. Baker also is looking at adding sound-dampening insulation to the nacelles.

Another idea is to turn down the turbines, essentially slowing the blades’ rotational speed. Sound measurement in decibels is a logarithmic equation. That means cutting the output from 45 decibels — the state standard — to 42 decibels would cut sound volume in half.

The problem, Baker said, is slowing all three turbine blades that much would reduce power output 20 percent. That would translate into electric rates that are 20 percent higher.

Another approach is to turn down the turbines only when the sound is most annoying. Computers can do this, Baker said, but it’s a complicated calculation. He has begun collecting sound and wind speed data and trying to correlate it to what neighbors observe.

“I am hopeful we can figure out how to turn these things down when the sound is most troubling,” he said.

That’s also the hope of the Island Institute in Rockland, a development group that focuses on Maine’s 15 year-round island communities. It sees renewable energy as critical to maintaining sustainable, offshore communities in the 21st century. With Baker serving as the group’s vice president for community wind, the institute is working with residents on Monhegan, as well as Swans Island and neighboring Frenchboro, on Long Island, on turbine plans.

These islands have fewer residents, so they don’t need as much power, according to Philip Conkling, the group’s president. That means smaller systems.

“I don’t think there’s going to be another three-turbine wind farm on the coast of Maine,” Conkling said.

He said it will take careful study to find a solution on Vinalhaven. Hundreds of people stood near the spinning turbines at the ribbon-cutting, he noted, and no one complained.

“But when you live with them day in and day out, it’s a different experience,” he said.

Bill would change standards

A proposed bill in the Legislature would amend current noise standards to include low-frequency sound. These sounds are emitted by wind turbines and blades, but aren’t addressed by the rules, activists say.

“Maine’s noise regulations do not require the measurement of this low-frequency sound,” Steve Thurston, co-chairman of the Citizen’s Task Force on Wind Power, said in an e-mail. “By using the dBA scale only, it appears that turbine noise diminishes to acceptable levels before it reaches homes nearby.”

Complaints from people living near projects in Mars Hill and Freedom show otherwise, the group says. Now the same pattern is emerging on Vinalhaven.

House Speaker Hannah Pingree, who grew up on North Haven, is following the concerns closely. She’s a big supporter of renewable energy, but has come to recognize that the Vinalhaven project is causing real problems.

“I am in a very active learning mode on this subject,” she said.

Pingree doubts the noise bill will get a hearing in this short legislative session, but the state should examine the issue, she said, perhaps through a special task force.

In the meantime, some towns in Maine are enacting ordinances requiring a mile between turbines and homes. After Art Lindgren and Ethan Hall related their experiences in Buckfield earlier this month, residents overwhelmingly passed a six-month moratorium, aimed at a three-turbine proposal on Streaked Mountain.

This trend worries Baker at Fox Islands Wind. A mile setback makes community wind energy unfeasible, he said.

“Do we want to set rules that makes it impossible to do something that’s really good for a community because 10 percent of the people are bothered by it?” Baker asked.

SECOND FEATURE:

Opposition seek moratoriums on farms; Some landowners have reconsidered allowing turbines

SOURCE: Green Bay Press-Gazette, www.greenbaypressgazette.com

By Scott Williams

January 24, 2010

People who don’t want a wind farm in southern Brown County are organizing, and they’re getting help from a group that has stymied similar projects in nearby Calumet County.

Dozens of homeowners and others in the wind farm development site have joined forces under the name Brown County Citizens for Responsible Wind Energy.

The group is urging local officials to impose moratoriums on wind farm construction in an effort to slow or stop Invenergy LLC, a Chicago-based developer planning to erect 100 wind turbines south of Green Bay.

The moratorium approach is credited with blocking wind farm development in Calumet County.

Although the Calumet County opposition group organized before landowners had agreed to allow wind turbines on their property, Invenergy already has signed contracts with many landowners in the Brown County towns of Glenmore, Wrightstown, Morrison and Holland.

But opposition being generated by the newly organized group is prompting some landowners to reconsider their participation in the $300 million Invenergy project.

Wayside Dairy Farm owner Paul Natzke said he and his partners have been impressed by the opposition, and now they are rethinking a deal to allow six Invenergy turbines on their 1,000-acre farm.

“Our biggest concern is splitting the community,” Natzke said. “That’s the last thing we want to do.”

Invenergy spokesman Kevin Parzyck said the company is aware that organized opposition has surfaced in Brown County. Calling some wind farm criticisms “myths,” Parzyck said the company would respond to such concerns during the state licensing process, which includes public hearings.

The developers also will talk individually with property owners who have heard opposition and are having second thoughts about being part of the project, Parzyck said.

“We can put them at ease,” he said. “We are very straightforward and honest with people.”

The developer has supporters in Brown County, too, partly because it is offering property owners at least $7,000 a year to allow one of the wind turbines on their property.

Roland Klug, a participating landowner, is so excited about the project that he has recruited other property owners to get involved.

Referring to opponents’ concerns about health and safety risks, Klug said, “That’s all a lot of baloney.”

Invenergy submitted an application Oct. 28 to the state Public Service Commission for permission to develop the Ledge Wind Energy Project in southern Brown County. The plan calls for 54 wind turbines in Morrison, 22 in Holland, 20 in Wrightstown and four in Glenmore.

With the capacity to generate enough electricity to power about 40,000 homes, it would be the Brown County’s first major commercial wind farm. It also would be larger than any wind farm currently operating in Wisconsin.

Supporters say the project would bring economic development and clean energy to the area, while opponents fear the intrusion and potential health hazards of the 400-foot-tall turbines.

Jon Morehouse, a leading organizer of Brown County Citizens for Responsible Wind Energy, said opposition has grown as more people learn of Invenergy’s plan.

Considering that the developers already have contracts with many landowners, Morehouse said he expects an uphill fight. But he said 100 people are involved in the group.

“It’s growing every day,” he said. “People are starting to see what’s happening.”

Members of Brown County Citizens for Responsible Wind Energy have approached town officials in Morrison and Wrightstown to request wind farm moratoriums.

It is a strategy that worked in Calumet County, where the County Board last year approved a countywide moratorium that has prevented any wind turbines from going up.

Ron Dietrich, spokesman for Calumet County Citizens for Responsible Energy, said a major wind farm likely would be operating in the county if his group had not organized and taken action. Although the success might be only temporary, Dietrich said it has allowed residents to study and debate the merits of wind energy.

“The process has slowed down,” he said, “and people are taking a second look at it.”

Brown County Citizens for Responsible Wind Energy plans a public forum on wind farms at 6:30 p.m. Feb. 18 at Van Abel’s of Hollandtown, 8108 Brown County D, town of Holland. For more information about the group, go to www.bccrwe.com.

THIRD FEATURE:

Note from the BPWI Research Nerd:

Click on the image below to watch a video about the wind farm mentioned in the following story and its proximity to the Horicon Marsh.

Better Plan has added underlined bold type to indicate direct links with interviews and videos featuring people mentioned in this article, for those who would like to know more.

Francis Ferguson is Chariman of the Town of Byron. In this interview, Chairman Ferguson is open about receiving money for hosting a turbine in the project, that his neighbor has repeatedly complained and made "a hell of a stink" about the nosie, and that the turbines sound like a jet plane. From a 2008 interview [Click here to watch video and read transcript]

Q. Do you think -- I guess in your opinion, do is a 1000 feet is a good setback?

Chairman Ferguson: It isn't any too much. Because my tower up here on the hill is a thousand feet from Hickory road here. A guy built a new home there in the woods. And he's made a hell of a stink. He's filed a written complaint and he's really fighting it right now.

Q Is he a thousand feet away?

Chairman Ferguson: Yeah. And he claims it's noisy and it aggravates him.

Q Do you notice any noise here?

Chairman Ferguson: You can hear it.

Q What does it sound like?

Chairman Ferguson: Sounds like a jet plane.

Scroll to the bottom of this post to watch the full interview with Chairman Ferguson

Wind farms cause controversy among community

SOURCE: Green Bay Press-Gazette, www.greenbaypressgazette.com

By Scott Williams

January 24, 2010

BYRON — Looking south from the home his father built, Francis Ferguson can see two generations of energy production in vivid convergence.

Locomotives chugging through this section of Fond du Lac County carry shipments of coal along the Canadian National Railway to be incinerated at nearby electric power plants.

Just beyond the train tracks, enormous wind turbines rotate on the horizon, working to harness a blustery winter day and convert that energy, too, into electricity.Ferguson, who was born here during the Great Depression and now serves as Byron town chairman, is philosophical about the old-style trains crossing through the shadows of a wind farm that sprang up just two years ago.

“It is a change,” he said. “You can’t sit and wait for the future to be the same as the past — it isn’t going to happen.”

Across town, Larry Wunsch stands beneath a 400-foot wind turbine towering over the home that he and his wife bought seven years ago because they wanted to live in the country.

Situated about 500 feet from Wunsch’s property line, the spinning giant casts a flickering shadow at certain times of day. It also occasionally emits a noise that Wunsch likens to a jet airplane.

At least a dozen other turbines dot the surrounding countryside.

Wunsch and his wife, Sharon, have stopped trying to live with the disruptions. They are getting ready to put their home up for sale.

“This is not for me,” he said. “It’s an invasion.”

For Tom Byl and Rose Vanderzwan, wind turbines are not only welcome, they are like home.

The young couple came to Wisconsin nine years ago from their native Netherlands, where wind energy has been part of the culture for generations. When developers needed locations in Fond du Lac County to erect wind turbines, Byl and Vanderzwan were happy to accommodate.

The couple, who have four small children, collect $17,500 a year for permitting three turbines on their Oak Lane Road dairy farm.

Some neighbors opposed to the wind farm are so upset that they no longer speak with Byl and Vanderzwan. But the couple makes no apologies.

“I really like them,” Vanderzwan said of the turbines. “I think they’re beautiful. And I think it’s a good idea to get some cheaper energy.”

Hardly anyone around here, it seems, is lacking in a strong opinion about wind farms, whether favorable or critical. Living on the cutting edge of energy policy reform does not lend itself to feelings of ambivalence.

Long after it began operating south of Fond du Lac with more than 80 wind turbines, the Forward Wind Energy Center divides residents as sharply as it did when the project was announced five years ago.

Opponents of the operations insist that wind turbines are jeopardizing people’s health and destroying the area’s peaceful aesthetics. Supporters, meanwhile, remain equally certain that wind energy is liberating the United States from both air pollution and dependence on foreign oil.

As state leaders push mandates for alternative energy sources, the debate that has absorbed neighbors here could soon reach a growing number of town halls. At least 20 other commercial wind farms are being planned or developed in Manitowoc County, Outagamie County and elsewhere.

One project proposed south of Green Bay in the towns of Glenmore, Morrison, Holland and Wrightstown would include 100 turbines, making it Wisconsin’s largest wind farm. Known as the Ledge Wind Energy Park, it would be built by Invenergy LLC, the same Chicago-based group that developed and operates the Forward project in southern Fond du Lac County and northern Dodge County.

With state public hearings expected later this year on the $300 million Brown County project, opponents are beginning to organize.

Invenergy vice president Bryan Schueler, however, said his company has found support for the project, which he said would be virtually identical to the Forward wind farm.

The company offers landowners compensation — typically $5,000 to $7,000 a year — for allowing a wind turbine on their property.

Schuler said wind farms draw public support not only because of the thousands of dollars paid to landowners, but because of economic activity resulting from the capital investment, construction activity and job creation. Residents also generally take pride in knowing that they are contributing to the growth of a clean energy alternative, he said.

“Every project will have some opposition, as with anything that is new to a community,” he said. “For every opponent, there’s usually many, many more supporters.”

When the Forward project was proposed in the summer of 2004, much of the opposition stemmed from its proximity to the Horicon Marsh, a wildlife refuge known for its populations of geese, herons and other birds. The 32,000-acre marsh is about two miles from the wind turbines.

Despite environmental concerns, the state’s Public Service Commission approved the project in 2005, and the turbines were up and running by 2008 in the towns of Byron, Oakfield, Leroy and Lomira.

The operation has the capacity to generate enough electricity to power some 35,000 homes.

Since the turbines started spinning, the state Department of Natural Resources says it has recorded bird and other wildlife deaths attributed to the wind farm at a higher-than-average rate.

Dave Siebert, director of the DNR’s energy office, said the national average for wind farms is slightly more than two bird deaths annually per wind turbine. As many as 10 deaths per turbine have been recorded at Forward. While his agency is not alarmed about the data, Siebert said officials hope to raise the issue when the Ledge Wind project comes up for regulatory review.

“Every next project, we learn a little bit more,” he said.

For many residents in and around the Forward Wind Energy Center, the biggest concern is how the turbines are affecting their quality of life.

Some residents complain that the spinning turbines are noisy, that they create annoying sunlight flicker, that they disrupt TV reception and that they destroy the area’s appearance.

“I think it’s ugly and noisy,” said Maureen Hanke, who lives in Mayville just west of the wind farm.

Gerry Meyer, a retired Byron postal carrier, is certain that turbines near his property have contributed to sleeplessness, headaches and other health problems for him and his family.

Saying that he turned down Invenergy’s offer of compensation, Meyer said: “I consider it bribe money.”

Others find the wind farm easy to tolerate — and even enjoy.

Alton Rosenkranz, who operates an apple orchard in Brownsville, said turbines positioned about 300 feet from his property generate the slightest “woof, woof, woof” sound. Rosenkranz said the noise does not bother him or his customers. In fact, he suspects the novelty of the wind farm is good for business.

“People come out to look at it,” he said. “And they buy apples.”

Many property owners receive payments of $500 a year from Invenergy if one of their neighbors has allowed a turbine to be erected too close for comfort.

Glenn Kalkhoff Jr., who lives in Byron, said the company also is providing him with free satellite dish service because he complained that turbines were disrupting his TV reception. Kalkhoff said he has no other complaints.

“You get a little whooshing sound once in a while,” he said. “That doesn’t bother me.”

Homeowners who have permitted Invenergy onto their property said the company is easy to work with and that the compensation has helped their families endure tough economic times.

But supporting the developers also has exacted a price for some in the form of lost friendships with wind farm opponents.

Byron farmer Lyle Hefter said he gets $10,000 a year for allowing two turbines on his dairy farm. He also received another payment — he will not say how much — to lease seven acres for a substation where Invenergy employees work.

Each of the turbines uses about one-third of an acre. Hefter said he has no problem working around the obstacles, and whatever noise they generate normally is drowned out by farm equipment, passing trains or other outdoor sounds.

“You don’t even know they’re here,” he said.

An organized group of opponents, known as Horicon Marsh Advocates, fought diligently to block the Forward project. The group no longer is active, but individual members remain vocal about their opposition.

Some opponents have made videos and kept other records to document what they consider the intrusive and unhealthy effects of living near a wind farm.

Curt Kindschuh, a former leader of the opposition group, said lingering disagreement has created lasting ill will among friends and neighbors. Kindschuh said he no longer is on speaking terms with a cousin who joined other landowners in welcoming Invenergy into the community.

Even at a family funeral long after the wind farm was approved, Kindschuh said, he did not share a word with his cousin.

“That’s the sad part,” he said. “There’s so many people out here with so many hard feelings.”