9/23/08 Life With Industrial Wind Turbines in Wisconsin Part 11: What happens when a farmer says no to a wind developer-

Ralph and Kevin Mittelstadt

Dairy Farmers

Fond du Lac County, Wisconsin

April 2008

Q: You were offered to sign a contract but you chose not to. How did that impact you and the community. Did it make any of your neighbors unhappy with you because of that?

Ralph: Many of the neighbors were unhappy. They sent us threatening letters.

Q: Threatening letters?

Ralph: Saying we owe them so much money because we're keeping them from getting money from these wind towers. Because we had an airstrip here, and originally, the Dodge County Board said that they should stay away 9,200-some feet, what the FAA said they should from an airstrip. Because we've been here 36 years with an airstrip. But evidently it didn't mean much because they just appointed other people to override them.

Q: Now these letters that were written to you by your neighbors, were they hand-written letters from the people themselves? Or were these letters coming from the company?

Ralph: They were typed-up from the company. The PR person. Form letters from a PR firm. [names firm] from Chicago, Illinois.

Q: Were they connected to the developer?

Kevin: Yeah. The developer, he's on the Carbon Climate Exchange. I don't know if you know about that. They're the ones trading carbon credits? He's onto that. And this PR firm worked for Al Gore. And too, himself, so there's kind of a tie.

Q: Do you know anything about property values, have you heard anything in the local community, are people concerned about property values being not maintained-- a drop in property values?

Ralph: I think the property values where the turbines are is going to drop. Because you have less work-land, number one, and any houses that were built up around them-- people don't want them in their back yard no more now, and so if they want to sell their houses, they ain't going to get as much money for it.

Q: Can you talk about some of the effects it's had on the community, you mentioned that neighbors are pitted against neighbors. Can you expand on that and tell us a little bit more about some of the effects on the local community because of the development?

Kevin: I'd say there's more hostility.

Q: More hostility?

Kevin: Yeah. In general, yeah. Money changes people.

Ralph: Our neighbor across the road had their house for sale and they had three different buyers on it. And every one that found out a wind turbine was going up in the back yard they backed right out of the deal.

Q: Has the house sold yet?

Ralph: No. They took it off the market now. They couldn't get it sold.

Q: Can't get it sold because of the development.

You mentioned the shadow flicker earlier, about the sun and the blades, can you talk about that a little bit, as far as what's that like here?

Kevin: If it lines up it will go over your whole yard, you know. It will come off your buildings.

Q: Does that happen every day? At a certain time?

Ralph: Just if it's clear out and the wind turbine is turned right.

Kevin: I guess if I was hosting a wind turbine I wouldn't put it east or west of my house.

Q: I had someone else mention that, because of the sun rising and the sun setting.

Kevin. Right.

Q: What was the interaction with the local officials like at the township board, or commissions who were appointed to approve this. Did you have a good feeling about working with them? Or did you not? Could you comment on that?

Ralph: They seemed to be sold out to the wind energy company already. Everything was just for the wind energy-- they wined and dined a lot of them ahead of time. And they're very positive about it. They don't want to listen to people. They think a lot of the complaints and stuff have no merit.

Q: You say you flew up to Minnesota to look at the project up there. Can you comment on that, as far as what your thoughts were when you took that visit up there.

Kevin: There's quite a few of them. And people up there seemed to be positive toward them, I guess.

Q: Is there much development, are they located around homes or around farms, or buildings, do you know?

Kevin: There's not-- it's not as populated as here. It's pretty sparse. More open.

Q: Was it a similar developer that was up there?

Kevin: There's quite a few of them. It's all different. Some of it is actually owned by farmers. On their own. There's actually a wind turbine manufacturer that moved in the pipes, I believe. The built the propeller blades there. So it's actually benefiting the community there.

Q: So your decision not to participate [in hosting a turbine] was an individual decision. Do you think if they were to do it differently in this area with a different development you would still participate in it?

Ralph: Probably not.

Kevin: No.

Ralph: I think someday if you could have a small one to generate your own current to the house, maybe it wouldn't be a bad thing. If they could prove it's efficient enough. But I don't think they can prove it yet. That it's going to be efficient enough to generate enough for a home.

Kevin: We own 450 acres. We took most of the fence lines out ourselves, you know? By hand. Moving all the rocks. So, we didn't really want nobody putting a road through the middle of it.

Q: Do you have any thought in general about the efficiency of wind-power?

Ralph: I think they shoot a lot of figures at you showing they produce more electricity than they really do. And in this area here, Wisconsin, only got wind enough for--what-- 21% of the time?

Kevin: I think 24%. or 30. The always give the figure that it produces so much-- like 63,000 homes this is supposed to provide power for.

Q: That's at 100%

Kevin: But they never tell you it takes a 25 mile per hour wind to make that. So the power curve is pretty sharp on a wind turbine. When the wind drops off it goes down dramatically. So, on average they're not going to produce very much power.

Ralph: It takes a little over 8 miles an hour just to start producing electricity. So the turbine can be turning out there, and not doing nothing. And up at Calumet, up here, what was that guys name up there?"

Kevin: Dean [Last name}

Ralph: He said that they brought that up at the meetings. They wanted them to shut the turbines down if they ain't producing electricity, and he said these people just jumped right off of their chairs. Because they want to keep these people that are seeing these turbines turning believing that they're making electricity all of the time.

Kevin: The average person sees them turning and they hear that figure that it's going to produce power for 66,000 homes-- and they're thinking, "Well, this is great."

Q: So you've attended a lot of meetings and have been quite involved with this process right from the start, then.

Kevin: I think we were the first people that they called. Because of the airstrip.

Q: You feel, you mean that the knowledge you've attained has put you in a position where you know what you need to know about it?

Kevin: Yeah.

Ralph: There's always more to learn, too. There's always more to learn about it.

Kevin: I mean, we're open minded. Like you said, we have the test tower, and we gave them a fair shake,

Q: How do you feel about the development here, now that it's here. How's it make you feel to see this here?

Ralph: It's a mess. It's a mess now. I don't know if they are going to get it straightened out in time for these farmers here, they want to put their crops in in the spring.

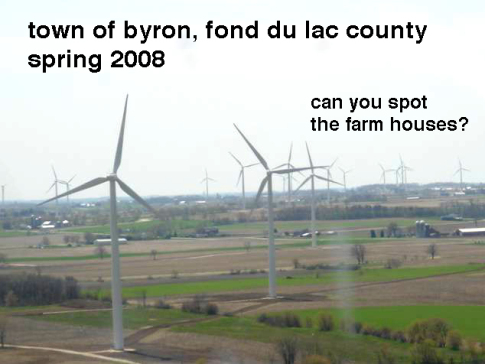

Kevin: It changes the view, I guess. That's what people always tell me, because, you know, we live here, so I don't really get to see it from far away distance, but they say, "We can see it from Beaver Dam"-- or Fond du Lac, or Lake Winnebago.

Ralph: From Oshkosh they can see this down here, you know? They can see it from Oshkosh.

Q: The state-- or I guess it was the Public Service Commission, that would be the agency. But they don't give much credence to what people think about aesthetics-- how things look. Any comments on that?

Kevin: I guess they really don't care if a couple people don't like the way it looks.

Q: Is there more than a couple people that don't like the way it looks?

Ralph: Oh, I would say if it would come down to a referendum, vote from all the people, I think it would be kind of marginal if it would go through. But it didn't come down to that. And it should have, I think. I think the whole township should vote on it.

I think that would be a good thing. To get all the people to vote on it one way or another.

It's just a couple of people that are on the town board. And you should bring that out and make them aware of all of the problems-- and the good things-- if there's good things about it, I mean, bring them all out. It should be the people that make the decision. Not just a couple of them.

Kevin: There was a couple of people that spoke up you know, and thats fine if they want to build them, but the town and the county should actually benefit from it, you know. Instead of losing all this money that's going away from the town and county. Because it does effect-- like you said-- all the people can see it and it affects you I guess.

9/21/08 Life with Industrial Wind Turbines in Wisconsin Part 10: What happens when a farmer says no to wind developers?

For those whose internet connection isn't fast enough to view this video, a transcript is provided below.

Life with Industrial Wind Turbines in Wisconsin Part 10Ralph and Kevin Mittelstadt

Dairy Farmers

Fond du Lac County

April 2008

Q: You both farm-- a family farm. Diary Farm?

Kevin: Dairy and cash crop.

Q: And you also fly [airplanes]?

Both: Yes.

Q: What can you tell us about you experience with this development in this area from when it started until today?

Kevin: We gave it an open mind when they came, and we decided not to go with the developer when it came down to it.

Q: You hosted a met tower on your land?

Kevin: Yes

Ralph: For a little over two years.

Q: What was the experience like working with that company with the met tower, was it a good experience?

Ralph: There was no problem with the met tower and it didn't interfere with the land too much because we put it on one of the fence lines. Only the diagonal cables that come off-- we had to look out for when we worked around it.

Q: What were some of the issues you found with your decision to not host a turbine. Did they give you any problems when you decided that you didn't want to participate in the project?

Ralph: The company?

Q: Yes.

Ralph: Yeah, they were very negative to us. They actually come out and threatened me. "Either you do this or we're going to put them around you." And he told us if we don't sign the contract, "we're going to put them all around you and shut you right down"

Kevin:[Our first contact was when] We got a call from the company in Illinois in 2002 and one of the guys actually came out here and we didn't know what was going on, this was the first we ever heard of it. Basically they said they knew of our airstrip because it's on the map,

and that if we didn't go along with what they were going to do in the future, they would build around you.

Q: What was your primary reason for choosing not to participate with the tower? Was it because of your airstrip and how it would interfere with that?

Ralph: I think, if there was any reason, one was we'd lose too much farmland, it would create a problem with flying, because propellers create a vortex and your plane becomes unstable and it pulls you down, so now we can't spray our crops and we're damaging so much good farmland, so we figured it wouldn't be feasible to even go that way because we'd be losing too much in agriculture.

Q: Now you have wind turbine around you. We look out the window here and you've got one here and another one over there-- have they affected your flying? Have you flown with them up?

Kevin: You wouldn't want to fly down wind of them.

They place them far enough apart--[the turbines] themselves so they don't create turbulence between the two so you probably wouldn't want to fly in between there.

Q: So is your runway impacted by this type of development?

Kevin: Yeah. They actually hired a pilot that was one of the friends of one of the lawyers to testify to the PSC that he flew down by Paw Paw Illinois [where there are turbines] and it didn't affect him when he flew. He came and testified, he was at all the hearings saying that it wasn't a problem. Had these graphics. What it would look like to have one next to your runway. Claimed that the buildings are more of a problem for a runway than a wind turbine.

Q: Because of the air flow?

Kevin: Because of the close proximity of our runway to the hanger there. [He said] it would be more of an obstacle than a 400 foot wind turbine.

Q: You mentioned this in this area-- there's a lot of crop dusting?

Ralph: We did have a lot of cash cropping. Peas and sweet corn.

Q: Can you tell us how that's changed and how this type of development is going to affect that?

Ralph: Well, the peas and corn are kind of going out if we can't spray with the airplane. Because it doesn't make sense to drive in fields where the crops are big already and run it down.

Kevin: The problem is-- like this last summer we had problems with the sweet corn, a lot of it blew over sideways-- and you can't get down the rows. So we lose an option.

Q: Are the other farmers in the area that are close to the wind turbines are they concerned about not being able to spray their ground?

Ralph: A couple of them. One of them that hosted turbines right here to the south of us asked the company if they would shut the turbines down when the crop duster goes through.

Q: What'd they say?

Ralph: They said no.

Q: What's your experience been, either with the local officials or the company. Do you feel like they came in here and they wanted to work with people or did they just come in here and disregard what people thought?

Ralph: They seem to come in and--- they put up a front like they are really trying to do something for you. But in the long run, they're going to stick you in the back it seems. And they want to turn neighbor against neighbor. So that you can fight amongst [yourselves] and then they can come out and sit back and be the winners.

Q: Let me ask you a couple of questions about the quality of life. You mentioned you talked to your neighbors. Can you comment at all about the noise or the sound or what it sounds like or what other people have thought about that?

Kevin: When the winds over 12 miles an hour it sort of sounds like a jet engine. It's a deeper tone, you know, a deep roar.

Q: Does it keep you awake at night, does it wake you up? Does it affect people's sleep patterns?

Ralph: You can hear it when you're outside. But now it's winter and we don't have our windows open. So that's going to make a difference. When you're outside you can hear it constantly.

Q: What are the setbacks like around here from a home. This [turbine] here you mentioned is 1000 -1500 feet away?

Kevin: I think that's the minimum. [1000 feet]

Ralph: That's the minimum

Q: Do you feel that's adequate? That they should be set father away?

Ralph: I think they should be set farther away from the home. At least 1500 feet. At least.

Q: And do you know, are there any benefits to the local community? The landowners here are getting paid, and the community is getting paid-- is it creating any jobs? We're asking people questions on jobs because at the state level, they're saying these kinds of developments are going to create jobs. Can you comment on that at all? Are they going to create any jobs for the local economy.

Kevin: They said they were going to hire a couple of people to service them.

Q: Local people?

Kevin: I don't know. It would have to be specialized I guess. You would have to have some kind of training.

Ralph: They do hire some local contractors who come in and do the gravel work.

Q: So construction jobs.

Kevin: In the construction phase there's lots of jobs. There were at least two hundred people worked on it or better.

Ralph. But it's short term. Once it's constructed now, [it's over]. We would like to see it be more local. Because we have quarries right here. But they bypass them and they go to the big operators. The big construction outfits that they can get it cheaper with, you know?

Q: Can you tell us a little bit about the access roads [to the turbines], how they're put in and what they look like and what they've done to the farm fields?

Kevin: They put 90 feet of culvert in, and put (breaker rock?) down and top over road gravel.

Q: And how much land area does that take up when they go in there? How many acres of land do these access drives take out of a typical farm field?

Ralph: I would say it's pretty close to five acres per turbine.

Kevin: It depends on how far back in the field they go.

Ralph: And how many roads they go through the field with.

Q: Is that disrupting the farming activity for the local farmers here having their fields divided up?

Kevin: I would say yeah. I mean the general trend in farming is bigger and bigger, wider equipment, so you're going have to be inefficient I guess when you're farming smaller fields. Especially with GPS, we just adopted that last year, so you're going have to go around stuff instead of in straight lines.

Q: As far as the contracts-- you were offered to sign a contract. What was your thought about the context of the contract?

Ralph: Very one-one sided. They're in control of everything.

Q: So if you own a piece of property as a landowner and the developer comes in and you sign an agreement with them, do you have any control over where they're going to put these access drives in or where they are going to place the turbines, or do you have any say-so?

Ralph: There it would depend on the company, I think. Because each company has different contracts. There are some companies that are a lot better at understanding, and work with the people. But the one we happen to have in this area I don't think is very nice at all.

Kevin: Just a couple of farmers that we know they said they weren't happy with where they put the stuff. They said there's no leeway in where they can put it. So they either had to go along with it or that was the end of it.

9/16/08 Life with Industrial Wind Turbines in Wisconsin Part 9

Scott Smrynka

Diary Farmer

Lincoln Township, WI

April 2008

Scott Smrynka speaking about stray voltage trouble on his farm: [Video image: an ohm reader with flickering numbers] This is a five hundred ohms resistor here, this wire is hooked to my stall, this white wire is a remote ground rod way across way, way away from the buildings. So I can go shut the power off across the road and this will still read the same. So it's coming out of the earth. And I'm four wired. When I shut my power off all four wires are disconnected. So my ground and neutral don't even come to the farm either.

This is coming out of the earth getting on my stalls, and this is where the cows are living.

Q: What kind of impacts are you having?

Low milk production, health issues, reproduction problems, cows dying of cancer and stuff like that. And more of it. More than normal. This [points at ohm meter] before we started was 5000. When the windmills went on, that was 5000. And we've got it this low. By doing a lot of different things that I'm going to keep to myself.

The utility has been out on this farm numerous times. Every time they come in this yard. An hour before they come in this yard [points to ohm meter] this goes to zero. Before they even do anything. And then when they leave, maybe a day or the weekend, it goes back to whatever is coming out of the earth. So they can clean this up. It's just they can't keep it clean, for one thing. Can't keep it low enough for one thing. You're just battling with them all the time.

Another thing, our meter's right there for-- we check the water meter for how much water the cows drink. Cows this size, when we were milking before, we were getting 30-35 gallons of water in these cows. Now we struggle to get over 22 gallons a cow. That's the milk production. You can't get the water in them. You need the water to cleanse their body, their whole system --digest the food.

Every animal that dies on this farm gets autopsied. Calf, cow-- tear it apart, we want to know what's wrong. What'd she die from. What happened? And what we've seen-- the organs-- the heart was inflamed --the kidneys-- the liver blackened and a lot of-- the biggest thing that seems to come out is the colostrum salmonella. They die from it. It's frustrating. What I'll tell you to make it very simple is it microwaves you from the inside out. That's what it's doing to our cattle.

You say, what human issues does it have? I'm no scientist, but what I see in my cows gotta be affecting me too, and my family. I mean what you're seeing with these cows-- reproduction and production----- they had the Univeristy vets out her from Madison, saying my cows only laid down 8.3 hours a day and a cows supposed lay down 12 to 14 to 16 hours a day-- I'm only getting half that. It's affecting -- that's why they ain't reproducing. The reproduction isn't there, the production isn't there. So 8.3 hours. That's all these cows lay down. They don't want to lie down. That's why I'm losing the milk production. And another thing we had a university vet come out here and stood right here by the return alley as the cows were being milked and said 33% of our cows are lame. We'll if they ain't laying down, they're going to be lame, right? And then you ask these vets and the utility and that, ok, you had these studies done, and that's what they're saying-- what are we going to do?

They're saying my stall design needs to be changed. I got three layers of rubber mattresses under these cows feet. How can I get it any softer. Stall design. You can see there's nothing in front of them. When they lunge they can get up and do whatever they want. And the other two groups of cows are in sand bedding, so if they're in sand bedding that's as soft as you're going to get. So I told them I wouldn't buy it.

Then the vets asked me, what do you think it is? I said, "Right here."[pointing to the ohm meter] You get that down and I guarantee these cows will lay down. Because at times we get it low. Really low.

And there's times when I got in trouble here, three four years ago, I clipped a lot of ground rods across the road. Stayed like that for 14 months. This meter went way down. My cows went up twenty pounds of milk, these issues weren't here. Until the utility found it, put it back together.

Q: So you know where it's coming from.

I know where it's coming from. I have no doubt in my mind. And I had a 30,000 pound heard average before those windmills were up. Now I struggle to get 20,000.

So I mean, it' all boils down to stray voltage--- or I'm not going to call this stray voltage-- ground currents or electrical pollution. There's more to this story than they let the people know. There's a lot we don't know. It's amazing. I just came across it while I was catching this stuff, and trying to figure out and solve my problem, using transformers, you name it. So I mean, what you guys gotta do is do a lot of research. If they're there [the wind developers], pounding on the door, and got permits from landowners and all that, then you're kind of screwed. Because their foot's in the door already. You gotta do this before they get their foot in the door.

9/15/08 Life with Industrial Wind Turbines in Wisconsin Part 8 and also the scale of the turbines

Today's featured interview is with one of the town supervisors in Calumet County's town of Lincoln where there was so much trouble with the noise from wind turbines that the utility which owned the turbines bought two homes and demolished them. People who lived in two other homes sued the utility and won an undisclosed out-of-court settlement. Until wind developers and the state of Wisconsin take people's lives into account when they site 40 story turbines 1000 feet from people's homes, this story is bound to be repeated as it is being repeated right now in Dodge and Fond du Lac Counties.. For those whose internet connection isn't fast enough to view this video, a transcript is provided below.

Life with Industrial Wind Turbines in Wisconsin

Part 8

Arlin Montfils

Township Supervisor,

Town of Lincoln, WI

April 2008

Arlin Montfils: We knew nothing, really, about them. The company said, well -- they imposed an 800 foot set-back from the nearest resident.

Q: Not from their property line, but from their home.

The nearest resident. I believe that's what it was. I haven't looked back for sometime, but in my opinion that was way too close, we had people that complained: noise, noise, and noise.

And it wasn't at high wind speeds. It was at low wind speeds like lets say ten to fifteen miles an hour, something like that, that's where the most noise was coming in.

The decibel level [limit] was 50 decibels, we knew nothing about it. In my opinion it should have been 45. They threw out that number and they said you and I talking is 50 decibels and that's probably true. I don't dispute that. And they probably haven't exceeded this 50 decibel level, but it's constant it can go on for-- well, you know the wind-- it can go on for 24 hours or more and that's when you start getting complaints because it never goes away and that's when it gets irritating.

With this noise complaint, they set up a toll-free number you could call that day or night, twenty-four hours a day and file a complaint. Stating that there's noise and it sounded like this or it sounded like that

and what time of the day and approximate wind speeds, and that went on for about a year, I would say, that they had this toll free number up. Then at the end of the year what they did was contact these residential home-owners and offer to buy their property. Offer to buy their homes.

Q: They did offer to buy them?

Oh yeah. They bought two homes. There were five basic complaints all the time. So they bought two of the homes, tore them down. One party got a divorce so another person lived there, didn't bother her, what ever. The two other places, they brought a lawsuit against WPS, they settled, I think they settled out of court, because if they had settled in court it would have been public record and we were not able to find out what they settled for.

Q: Are they still living there?

They are still living there. Yes.

Q: Now you mentioned, the public utility-- two of [the houses] they bought and they tore them down. Why do you think they tore them down rather than try to resell them?

If they sold them they might have sold them to someone who would still complain. And they didn't want complaints, I guess. One of those situations where the person got a divorce, and he came out on top by selling it to them, and the other party just sold the house.

Q: Being a public official you hear a lot of things. Do you feel that the complaints from the property owners were valid?

Oh yeah. Sure.

Q: They were valid.

Yeah. They'll say you only got one home complaining or two well the turbines are right here, there are eight of them, there's only two homes close by. So you had two complaints. So they say "You only had two complaints" but if there was more homes-- if there was then homes, you'd have ten complaints.

Q Do you expect to have anymore development for wind turbines in this area?

No. They companies that put them -- the utilities-- won put them up anymore. But if they were to do it, they would have private companies do it and then buy the electricity back from them.

Q: Why do you think they are getting away from the development themselves and having a company do it--

They want to be good neighbors, so if they don't do anything about a complaint they are not good neighbors. So if they deal with a private company, the private company would have to deal with all the complaints or issues or what have you, they would have no problem. That's what they told us. It's a lot easier to have a private company put them up rather than themselves.

Q: Getting back to the economic side of this did this development, other than bringing revenue in to the local township and county and the landowners, did it bring any jobs here?

When they were first building, a private contractor dug the base and I'm sure they got the concrete for the bases from a local supplier.

Q: Other than construction were there any jobs created?

No. No. They do have-- they found their own personnel for maintenance, you know. And if there is a problem with that they come in with their own companies or who ever they have

Q: Specialized?

Basically, they come in with a high crane you know. And we don't have that. Nobody around here has that. So they have to come in with it. Private company from someplace. I don't know where.

Q: Have there been any maintenance issues with the turbines?

I believe there is. We get a report every year as to what was replaced. Basically it's the generators and the oil sometimes a bearing goes out, they have to replace that. It's all them. We have nothing to do with that, you know.

Q: Can you tell us a little bit about the benefits to the community or pros and cons that you can see on both sides of this for your community?

Financially it's the biggest benefit there was for the township.

Q: For the township?

Yes.

Q: Was it a needed revenue stream?

No. We could have done without it.

Q: But it was nice having extra--

Oh, absolutely

Q: It's always nice to have extra money

Right. Yeah.

Q: So the money, the financial aspect of it is a benefit. What about cons? Is there any negative impact?

We had a person that complained a lot about stray voltage. The party himself spent a lot of money trying to control the stray voltage on his place.

Q: Did he have livestock?

Oh yeah. He's a dairy farmer.

Q: Big dairy farmer?

Oh yeah. A hundred and fifty cows he might milk plus other animals, you know. He spent a lot of money, you know. He couldn't alleviate it, but could control it.

Q: Did the development company, did the public utility do anything to assist him with that?

No. We did have the Public Service Commission of Wisconsin come in and do testing, and their tests came back saying the towers are within guidelines--I don't know what the guidelines are--- that they did not exceed the guide lines toward stray voltage. [The farmer's] concern was they did.

Q. Have you heard of any health concerns people had because they are living next to them.

Well this party that put their home up for sale --they thought there kid was getting too many headaches.

So they did have Madison Gas and Electric, the owners of those utilities, they did come in and do a study, and what ever their findings were, they said they did not exceed guidelines for homes, for residential homes for as far as stray voltage went. That's as far as it went.

Q: My other question here is information made available on the internet. There's a lot of information

about Lincoln township that's available on the internet now for people to view and consider. What are your thoughts about that information, is it factual information? An accurate representation of what's taken place here?

I have not seen it. I don't have internet access right here, you know. But I know about it. Basically what I'm telling you now, if you want to compare what I've said to you to what's on the internet? Work from there. I think it's pretty factual, I think they exaggerated on some things, I don't know which ones it would have been, but, yeah. It's reasonably accurate I think.

NOTE FROM THE BPRC RESEARCH NERD: Below is a link to a short film which shows the scale of an industrial wind turbine compared to things we ordinarily see in our lives. It also includes images of an actual turbine being built at night in Fond du Lac county in the winter of 2007-2008. For those whose internet connection isn't fast enough to watch it on line, still pictures from the video are provided below.

9/13/08 Life with Industrial Wind Turbines in Wisconsin Part 7 and the Heartbreak of the Horicon

Q: So what can you tell us about the wind turbines in this area here? What's your experience with them? Have you had any adverse effects.

Dan: The only thing is the noise--

Julie: Well, first of all it's an eyesore this used to be all country. They have these red lights and they all seem to flash at the same time, so you feel like you're living in the middle of an airport. Actually, I call it an industrial park. I now feel like I'm in the middle of an industrial park. And they do make noise. We're getting a southwest wind. If you walk over there you're going to hear these two [points to turbines] making their noise.

Q: I hear some noise right now. Is that what I hear?

Julie: Yeah. That's not an airplane, that's the wind turbine. Step over here. There's two of them back here. You hear that?

Q: That's loud.

Dan: I can hear it at night when I'm laying in bed.

Julie: We have a brand new addition right in the back of the house and you can hear that.

Q: Now, you have your house up for sale. Is it because of the wind turbines?

Julie: It pushed us-- it's not the only reason, we want to get closer to our family--- but it pushed us to giddy-up and get out. Because we knew it when it was peaceful-- you'd hear the birds, the wind, and now we got this. And maybe somebody might not care, there's people who live along highways and airports and maybe they don't care but we knew what this place was like.

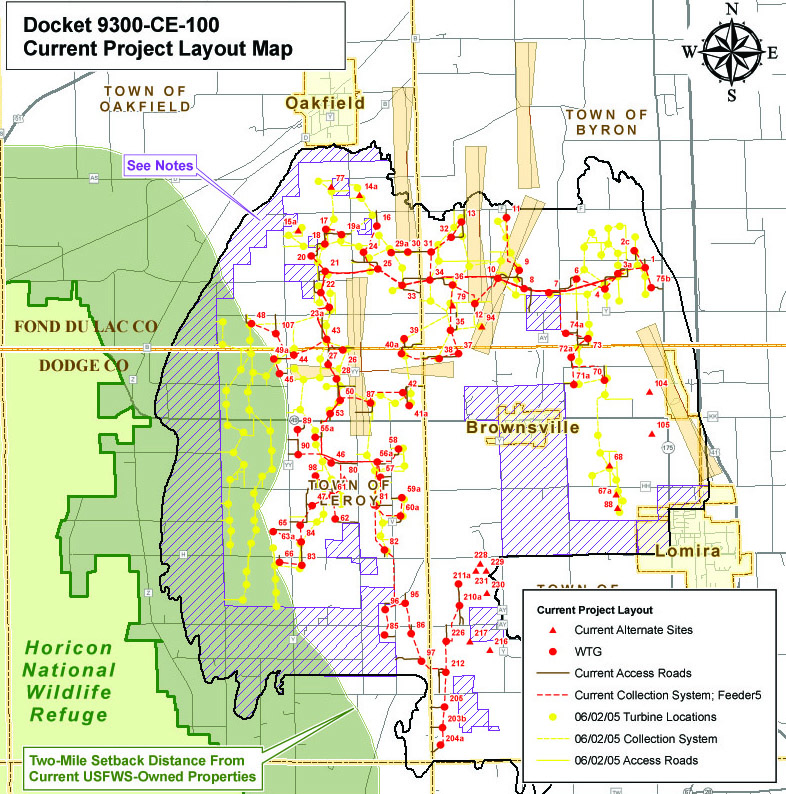

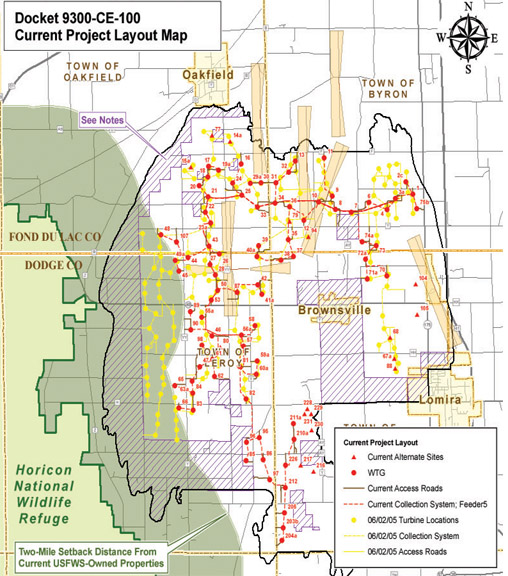

NOTE FROM THE BPRC RESEARCH NERD: our second video is about what is going on at a national wildlife refuge called the Horicon Marsh which is just two miles from the 86 turbine wind farm these people are have been forced to live with.

NOTE FROM THE BPRC RESEARCH NERD: our second video is about what is going on at a national wildlife refuge called the Horicon Marsh which is just two miles from the 86 turbine wind farm these people are have been forced to live with.

The turbines were built just two miles from

the marsh, which is considered to be a wetland of global importance for wildlife and nearly 300 species of birds, some of which migrate seasonally and others which make their year round home in the Horicon Marsh. If

not for the efforts of concerned citizens, the wind developers would

have put the turbines much closer.

Wind developers downplay the effect of industrial scale turbines on wildlife, saying that wind energy's role in the reduction of green house gases is a fair trade for bird and bat deaths. But because wind turbines rely on fossil-fuel burning power plants in order to function, the National Academy of Sciences determined that that wind energy's impact on the reduction of CO2 emissions is negligible. Danish studies show the same conclusion. Wind energy is the only renewable resource that keeps us tied to fossil fuel and transmission lines. In the 2009 legislative session there will be a push for wind turbine siting reform. This will take away the power of our local governments to have any say about where wind turbines can be located in our communities and hand this power to the PSC. There is no provision for the protection of wildlife in the Wisconsin draft model wind ordinance which the PSC supports. Contact your legislators and ask them why this is? And visit the Horicon Marsh Systems Advocates website at hmsadvocates.org to find out how you can help.