6/20/09: A Darker Shade of Green: Wisconsin State Journal Reports Wind turbines among the troubles for the Horicon Marsh, and Better Plan takes a closer look at the Horicon bat and bird mortality study conducted by the wind company

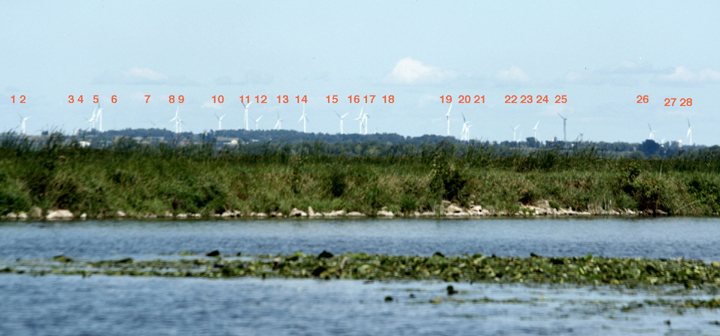

Turbines along the Horicon Marsh 2008 photo by wind farm resident, Gerry Meyer

Turbines along the Horicon Marsh 2008 photo by wind farm resident, Gerry Meyer

Water Woes, Wind Turbines, Threatening Horicon Marsh, Report Says

June 20, 2009

Wisconsin State Journal [click here to read at source]

Nearby wind turbines, declining water quality and decreasing water levels at Horicon National Wildlife Refuge in southeastern Wisconsin earned the popular birders’ destination the dubious distinction of being ranked the third most imperiled refuge in the nation, according to a list compiled by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility.

Released every year and based on interviews with refuge staff, the list ranks the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska and the Hawaii Islands National Wildlife Refuge Complex as the first and second most threatened refuges. PEER is a national alliance of local, state and federal natural resource professionals.

Located about 40 miles northeast of Madison, the 23,375-acre Horicon refuge is famous as one of the largest freshwater cattail marshes in the U.S. It’s an important migratory stopover in the spring for migratory waterfowl and has long been noted for the huge numbers of Canada geese — as many as 300,000 in the spring — that make the marsh a noisy place during their migrations.

But, according to the PEER report, pollution from the Rock River, which both feeds the marsh and drains large agricultural areas upstream, is poisoning the marsh with silt, phosphorus and agricultural chemicals. Silt carried by the river is clogging ditches and carrying nutrients that promote weed growth and cause cattail mats to grow out of control.

“In effect,” the report said, “the marsh is filling from the bottom up.”

A relative new issue for the marsh is the nearby construction of hundreds of wind turbines that may pose a threat to migrating birds. A company called Forward Energy received final permission from the Wisconsin Public Service Commission in 2005 to erect 133 wind turbines on the edges of the marsh. The turbines, 86 of which are already in operation, are 390 feet high from the base to the tip of their blades.

The uncertain impact of the wind turbines prompted another organization, the National Wildlife Refuge Association, to name Horicon one of the nation’s most endangered refuges in a list released four years ago.

Laura Miner, who oversees the turbines for Forward Energy, said the company is midway through a two-year mortality study at Horicon. So far, the results are “not alarming,” she said. During a four-month period last fall, researchers recovered less than 10 bird carcasses and about 70 bat carcasses near the turbines.

“We think the bird number is relatively low, and we have found no carcasses of federally protected species,” Miner said.

Diane Kitchen, assistant refuge manager for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said many refuges across the nation are facing water issues, both related to quality and quantity. “We have trials, like every refuge does,” she said.

As for the wind farms, Kitchen said it is too soon to determine whether the huge turbines pose a real threat to migrating birds.

The PEER report called for the following actions to lessen the threats to the refuge:

- Existing cooperation with farmers and agricultural agencies should be expanded to reduce water pollution problems.

- A 21st century marsh-management plan should be developed, funded and staffed.

- Scientific reviews should be conducted to help plan its future. Such studies should include research on wind turbines, which is already underway, and studies of hydrological problems by the U.S. Geological Survey.

— State Journal reporter Doug Erickson contributed to this report.

By Ron Seely

20 June 2009

Click on the image above to learn more about Wisconsin's Horicon Marsh, the largest cattail marsh in the U.S, and about the Forward Energy wind farm sited alongside it. [You can also see the video by clicking here]

A CLOSER LOOK AT THE BIRD AND BAT MORTALITY STUDY:

The developer wanted to site turbines just 1.2 miles from the marsh.

Environmental groups asked for setbacks of at least four miles.

In its final decision, the PSC chose two miles as the setback and agreed to reconsider the 1.2 mile set-back some time in the future.

The Public Service Commission of Wisconsin, it its decision to allow Invenergy's Forward energy project to be sited just 2 miles from the marsh, acknowledged studies which confirmed that "birds visit the wind farm site very heavily during migration seasons, and that the proximity to the marsh could cause greater than average avian mortality." (Docket 9300-CE-100 PSC Ref#37618, p.16)

But the financial concerns of the wind developer trumped the protection of birds and bats, citing the wind developer's fast-approching production tax credit deadline and concluding that more comprehensive pre-construction avian studies were not necessary or in the public interest. (Docket 9300-CE-100 PSC Ref#37618, P. 17)

The PSC also gave the developers a pass on bat studies, though one of the largest bat hibernacula in the state is located not far from the marsh.

The wind developer's paid witness, testified that pre-construction bat studies had not been required elsewhere, but at the Buffalo Ridge project in Minnesota no relationship between bat activity and mortality could be observed. (p.21)

The PSC agreed, and no pre-construction bat surveys were done. Instead, the PSC offered this trade off:

"The commission... finds that post-construction mortality research will advance scientific knowledge about the potential impacts of wind farms upon bat poplulations"

They now a have plenty of dead Wisconsin bats to work with.

Here are some of the protocols of this study:

(We thank the concerned party who passed this document to us for consideration. Download complete document by clicking here)

The search area around a turbine is defined by a 525 ft by 525 ft square, in which the turbine constitutes the center of the square.--

In other words, only carcasses found 260.5 feet in any direction from the turbine are considered.

The turbine's blade span is approximately 260.5 feet.

The tip speed averages over 100 mph.

A bird or a bat hit by a blade going 100 mph and knocked out of this search area would not be considered.

The people employed to search for caracsses are instructed to "Store the plastic zip-loc containing the carcass in the freezer at the wind company building upon completing searches for the day"

(Emphasis added) SCROLL DOWN to read the entire carcass collecting protocol sheet.

NOTE FROM THE BPRC RESEARCH NERD: It's hard not to have concerns about the wisdom of simply dropping off the carcasses at the 'wind company building'. It seems that an independently maintained site would be more a reliable depository.

(CLICK HERE FOR MARCH 7th 2009 news story)

LOOKING FOR A GREEN JOB?

In August of 2008, one of the 'green jobs' to be had involved walking six acres around five industrial scale wind turbines in the Forward Energy wind farm, looking for dead bats and birds.

The job paid $10.00 an hour plus mileage.

Click on the image above to see a video shot by some one who has this green job, telling us what her mornings near turbines were like, and gives us an candid look at just how post-construction avian and bat mortality studies are being conducted.

UPDATE: Since we posted this, the video has been pulled. Transcript of video below

The video is called, "What has been keeping me busy?" and does not appear to anything but an amiable personal video intended to update friends and interested parties. The dull roaring in the background is the turbine sound. It is sometimes faint, but always present.

The image below is the site map of the project. The two blue circles are the locations of specific turbines she mentions.

TRANSCRIPT:

"Good Morning.

It is now five am.

I'm going to show you what I've been doing lately that I haven't been on line. It's been awhile since I've been here, but I want to show you what I'm doing so you'll understand.

I don't know if you can hear the noise behind me but I am at..... I will show you... hold on a minute... we're going to go up, and we're going to go up, and we're going to go up, and you see those blades?

I am at the wind turbines.

There's one over there you can see a little better. And I am looking for dead birds and bats. And they've been finding bats lately. So we got some areas to walk and check for dead birds. And, let's go.

There's more wind turbines. More wind turbines. I'm checking the roads to see if there's any dead birds or bats. The sunrise is starting to come. Pretty.

But I get up at three thirty, every morning. Seven days a week. Get paid ten dollars an hour plus mileage. Let's look over here. Let's see if we can see those wind turbines over there. Just fields and fields of them.

So let's start looking. And if I find anything, I'll let you know.

There's a turbine I am checking. And what we have to do is, they have plowed or mowed areas for us to walk and we check both sides, and they go -- oh, four or five of them that we have to walk down and check for the birds. They have been finding a lot of bats. So that's what we're looking for.

Look at the sunrise. Beautiful. So peaceful out here in the morning.

Well we didn't find anything here, so we head to our next turbine. See you when we get there.

All right. We are at wind turbine 83. That last one we were at was 96. So we're going to check around here and see what we can find. And there's a lot more turbines up in this area so I can show you those.

They're going to build a hundred and thirty-six turbines...... the hill is just filled with them here....

there's one there, a whole field of them over there.

We're going to be looking in corn this time. Last time we were looking in soy. So let's head to the cornfields.

That turbine is pretty close to this one. Look at those blades. We're right under them. Yes, we're right in the middle of a corn field. This is sweet corn.

You can tell by tassels on top. They're whiter. Field corn is a darker brown. So this is sweet corn we're in. And you can hear the birds chirping.

And there's the wind turbine I'm checking right now.

I got to walk all the way down there. Actually at each turbine, you're walking six acres. Getting a lot of exercise.

There's my next turbine.

I know I look a mess. It's 95 percent humidity out there and right now it's 84 degrees. And with my hat on I was sweating up a storm. But I need to call Steve. He's a gentleman from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. And he's the one that hired me. They're doing a study for bats and birds by the wind turbines.

And we're also working with Forward Wind Project. And they're really nice guys.

OK I got a couple of more turbines to check-- and I'm going to say good-bye now and unless I find something I'll see you later. Buteverybody have a great day and we'll talk to all of you later. Bye.

(Later)

Good morning everyone..... I'm out doing another search this morning, and I'm actually having a lot of fun. Getting a lot of exercise. Walking six acres each turbine, times five, it's 30 acres I'm walking. So I'm getting a lot of exercise and I'm enjoying it.

I got a bat yesterday but my camera battery was dead so, sorry, couldn't get it to you. But, um, the wind turbines do not hit the bats with the blades.

If you're squeamish, and don't like to hear things happening to animals, skip the next 30 seconds.

[She pauses]

What's happening to the bats is they are getting sucked in and their insides are imploding. So. Yeah.

They are not getting hit by the turbines, they are getting sucked in by them and their insides just explode... imploding. So that's what's happening to those bats.

I haven't found any regular birds yet, but when I do they'll check those out too. They'll autopsy those.

The gentleman I'm working for, Steve, is working on his masters at the University of Madison. And his roommate who he's living with now is also going to school for wildlife...... preservation.

And he's doing a study on bats, so he's the one who did the autopsies on the bats and told us what is happening, actually. He is not finding any blade marks on them.

They kind of figured that's what's happening, because of what's happening, they found out they are imploding when they did the autopsy.

Yeah. How weird.

They are just getting sucked in and the pressure is so much that that's what's happening.

So I am on my way to my next turbine, and if I do find anything today, I'll show you.

Researchers say a pressure drop created by turbines can cause bats' lungs to burst

March 1, 2009 by Gerry Smith in Chicago Tribune

The mystery was alarming to wildlife experts: large numbers of dead bats appearing at wind farms, often with no visible signs of injury.

Researchers now think they know one reason: Wind turbines cause bats' lungs to explode. More specifically, a sudden drop in air pressure created by the blades can cause fatal internal hemorrhaging, researchers at the University of Calgary said in a study.

The toll taken on bats highlights a delicate balance facing the wind industry-how to be "green" without causing other unintended environmental consequences.

Some of the best sources of wind-coastlines and mountaintops-also happen to be in the path of migratory birds. Wind farms installed on mountain ridges also have triggered fears over soil erosion, and some environmental groups-citing land use laws designed to keep Mother Nature unspoiled-have fought proposed wind farms.

With the deaths causing a stir among wildlife advocates, an unusual partnership called the Bats and Wind Energy Cooperative is seeking ways to strike a delicate balance between protecting the bat population and meeting the nation's growing demand for renewable energy.

"We support the development of clean energy, but to make it 'green' we have to do everything we can to minimize the environmental impacts," said Ed Arnett, project coordinator for the cooperative.

Some wind experts dismiss fears over turbines' impact on wildlife. They point to a 2007 study by the National Academy of Sciences that concluded far more birds and bats have been killed in collisions with vehicles and buildings than in collisions with turbines.

But wildlife experts are particularly protective of bats because the mammals have low reproductive rates, meaning even small numbers of fatalities can affect their populations.

"Once you start taking a small number of bats out of the general population, the risk of endangerment or extinction vastly increases," said Joseph Kath, the endangered species project manager for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

Thus far, there have been no reports of endangered or threatened bat species being killed at wind farms in North America. Most bats felled by turbines have been migrating species like hoary bats, eastern red bats and silver-haired bats.

The concern over bats is fairly recent. Since the 1980s, when wind farms were in their infancy, wildlife biologists have been more worried about protecting birds from spinning turbines. Bat deaths at wind farms largely went unnoticed.

Then in 2003, researchers stumbled upon an estimated 1,400 to 4,000 bat carcasses at the Mountaineer Wind Energy Center in West Virginia and recorded extensive bat fatalities at wind farms in Pennsylvania and Tennessee.

Wildlife experts were taken by surprise.

"These are unforeseen circumstances," Arnett said. "Most of us didn't anticipate this being a problem."

Since then, the chorus of voices calling for greater protection for bats at wind farms has grown louder. Last summer, the American Society of Mammalogists called for wind farms to avoid "bat hibernation, breeding and maternity colonies."

Still, the explanation for why bats with no external signs of injury were being found dead at wind farms was largely a mystery until August.

That's when researchers at the University of Calgary reported that 90 percent of bats felled near one wind farm showed signs of barotrauma, or fatal internal hemorrhaging, of the lungs that occurred because of drops in air pressure near the spinning blades.

The condition affects bats more than birds because bird lungs are more rigid and can withstand sudden changes in air pressure, according to the study, which was published in the journal Current Biology.

The study may explain why bat fatalities often outnumber bird fatalities at wind farms. In Illinois, it is estimated three times as many bats (93) as birds (31) died during a year at the 33-turbine Crescent Ridge Wind Farm in Bureau County, a consulting firm reported last year.

The firm, Curry & Kerlinger, deemed the findings "small and not likely to be biologically significant."

But given a decline in several bat species in the eastern United States, "the possibility of population effects, especially with increased numbers of turbines, is significant," the National Academy of Sciences study stated.

Illinois is expected to increase the number of wind farms dramatically in coming years. The state has mandated that 25 percent of its electricity be generated by renewable resources by 2025, with about 75 percent of that renewable energy coming from wind. Illinois has 915 megawatts of capacity installed with the capacity to build 9,000 megawatts.

Arnett said the cooperative doesn't discount the Calgary study but has conducted studies of its own, using night-vision cameras, that found bats also have been killed by collisions with turbine blades.

There are several theories as to why bats might be flying close to turbines. Some think bats might confuse turbines with large, dead trees because many species found dead use such trees to roost. Others hypothesize that turbines may attract insects, which attract hungry bats.

The cooperative has been looking for ways to bring down the death toll, including studies of the effectiveness of ultrasonic sounds that would deter bats and curtailing the spinning of turbines until it's too windy for bats to fly.

Arnett said the latter step may have some economic consequences. But he expressed confidence that the wind industry can continue to grow without harming bat populations.

"It's not choosing one or the other," Arnett said. "It's finding a balance, and I'm convinced we can solve this problem."

Web link: http://www.chicagotribune.com/features/lifestyle/g...

EXTRA CREDIT:

Here's how the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service website describes the Horicon Marsh:

"At over 32,000 acres in size, Horicon Marsh is the largest freshwater cattail marsh in the United States. The marsh provides habitat for endangered species and is a critical rest stop for thousands of migrating ducks and Canada geese. It is recognized as a Wetland of International Importance, as both Globally and State Important Bird Areas and is also a unit of the Ice Age Scientific Reserve."

"While this marsh in renown for its migrant flocks of Canada geese, it is also home to more than 290 kinds of birds which have been sighted over the years. Due to its importance to wildlife, Horicon Marsh has been designated as a "Wetland of International Importance" and a "Globally Important Bird Area." Horicon Marsh is both a state wildlife area and national wildlife refuge"

The Public Service Commission of Wisconsin, it its decision to allow Invenergy's Forward energy project to be sited just 2 miles from the marsh, acknowledged studies

Here's the complete protocol for the bird and bat mortality data for the Forward Energy wind farm along the Horicon Marsh:

I. Defining the Search Area:

A. The search area around the turbines is defined by a 525 ft by 525 ft square, in which the turbine constitutes the center of the square.

All of the plots are located within active agricultural fields throughout northern Dodge and Southern Fond Du Lac counties.

The total area of the plot is equivalent to 6.3 acres; the corners of the square are marked by 6 foot bamboo stakes with iridescent marking tape.

The transects cut into the square represent the 1.1 acre search area searchers are responsible for. Plots that are not at the proper vegetation height to be cut will contain two bamboo stakes 15 feet apart on both sides of the square.

These stakes create a lane in which searches should take place; these lanes will later be mowed when the vegetation height is at the proper level.

There are a total of five mowed transects within the plot, and the sixth transect is made up of the access road leading up to the turbine and an extension of this access road mowed in the plot.

The transects are approximately 525 feet long. Each segment born perpendicularly from the access road and its extension are half the length of the transect, or 262.5 feet.

Maps will be provided on the back of the data sheet with significant land marks, property lines, crop types, and the search transects and the access road with its mowed extension denoted.

While most of the transects are cut perpendicular to the access road and the access road extension, exceptions will be noted on the map for the specific turbine.

II. Data Collection: Pre-Search

1. Searcher: Record your name, including first and last name

2. # of Searchers: Record number of searchers, if alone record “1”

3. Turbine #: Record proper turbine number

4. Date: Record date

5. Start Time, End Time & Total Time: Record the time at which you start and finish the search, then subtract to determine total

6. Wind Condition: Record the wind condition on site, choosing from three codes

a.Calm (C) : Air is still, no vegetation movement, no feeling of a breeze

b.Light (L) : Slight breeze, approximately 1 - 15 mph, vegetation waving

c. Strong (S) : Obvious stronger winds, pre-storm weather conditions, 15 mph and up, heavy gusts of wind

4. Cloud Cover: Determine and record cloud cover, choosing from three codes

3a. Clear (CL) : No visible clouds in sky, “blue” skies

b.Partly Cloudy (PC) : Some clouds, not stormy but simply cloudy, some sunshine

c. Overcast (O) : Many clouds in sky, often grey, pre-storm or pre-rain weather conditions

*Do not confuse morning fog with clouds, skies may not necessarily be overcast when fog is present

5. Is the top of the turbine visible?

a. Circle “YES” if the top of the turbine is visible (no low-lying fog)

b. Circle “NO” if the top of the turbine is not visible (fog is at least 200 feet off the ground, generally foggy at ground level

6. Precipitation

a. Circle “YES” if there is precipitation of any degree

b. Circle “NO” if there is no precipitation

III. Searching

A. The searcher is to walk the 6 transects, consisting of 5 mowed or staked transects and the access road and its extension. While walking the transects, search the ground covering the entire 15 foot wide transect for dead birds and bats. Keep an eye out for abnormalities in shape and color on the ground substrate.

B. Walk at a pace conducive to the likelihood of finding carcasses, approximately 15 to 30 minutes per turbine depending on plot design.

IV.Collecting

A. Upon locating a carcass, record the Carcass Condition Rating

1. Carcass Condition Rating

a. Fresh (1) : The bird or bat appears to have recently expired, limited decomposition or scavenger impact, relatively decent condition

b. One to 2 days old (2) : Partially scavenged, usually by insects and their larvae, slightly decomposed but still in reasonably good condition

c. Decomposed (3) : The carcass has obviously been on the ground for a while, often decomposed down to fur/feathers and bones

d. Canʼt Be Determined (4) : The rating of the carcass can not be determined due to factors such as heavy rains, flooding, human interference, etc...

B. If camera is available, take a picture of carcass where it lies as well as a picture with the wind turbine in the background and the carcass in the foreground for estimating distance

C. Indicate the approximate position of the carcass in relation to the turbine by placing the number of the carcass in a square on the grey scale transect, each representing 15 feet, at the estimated distance from the turbine (Refer to Fig.1)

D. Next place the carcass in a zip-loc plastic bag and label the bag with the Carcass ID

1. Carcass ID

a. The Carcass ID consists of a single number composed of the turbine #, the date, and the # of the carcass in order of carcasses found that day. The count for carcasses

are renewed each day. For example, if 2 bats are found on the same day, at turbine 37 on August 2, 2008, the Carcass IDs would appear like so:

37-8/2/2008-1

37-8/2/2008-2

E. Store the plastic zip-loc containing the carcass in the freezer at the wind company building upon completing searches for the day (Be sure to label all bags properly

before placing in freezer)

V. Data Collection: Post Search

A. Vegetation/Visibility Scale

1. Good (1) : Transects do not need mowing, carcasses visible, easily found

2. Needs mowing in a few days (2) : Carcasses becoming harder to find, level of vegetation impairing (usually with hay, grass, and alfalfa)

3. Needs mowing ASAP (3) : Carcasses underneath vegetation, vegetation height higher than 6 inches, dense vegetation

PROTOCOL SUBJECT TO CHANGE AMENDMENTS WILL BE MADE AND SEARCHERS WILL BE PROPERLY NOTIFIED AND TRAINED, AS THE STUDY EXISTS IN AN ADAPTIVE PROGRESSION

For more information: Refer to Data Sheet Example

Store the plastic zip-loc containing the carcass in the freezer at the wind company building upon completing searches for the day (Be sure to label all bags properly

before placing in freezer)