Entries in wind farm setbacks (66)

1/9/12 Why should wind turbine setbacks be measured from property lines?

Why do wind turbine setbacks need to be measured from the property line?

Why do wind turbine setbacks need to be measured from the property line?

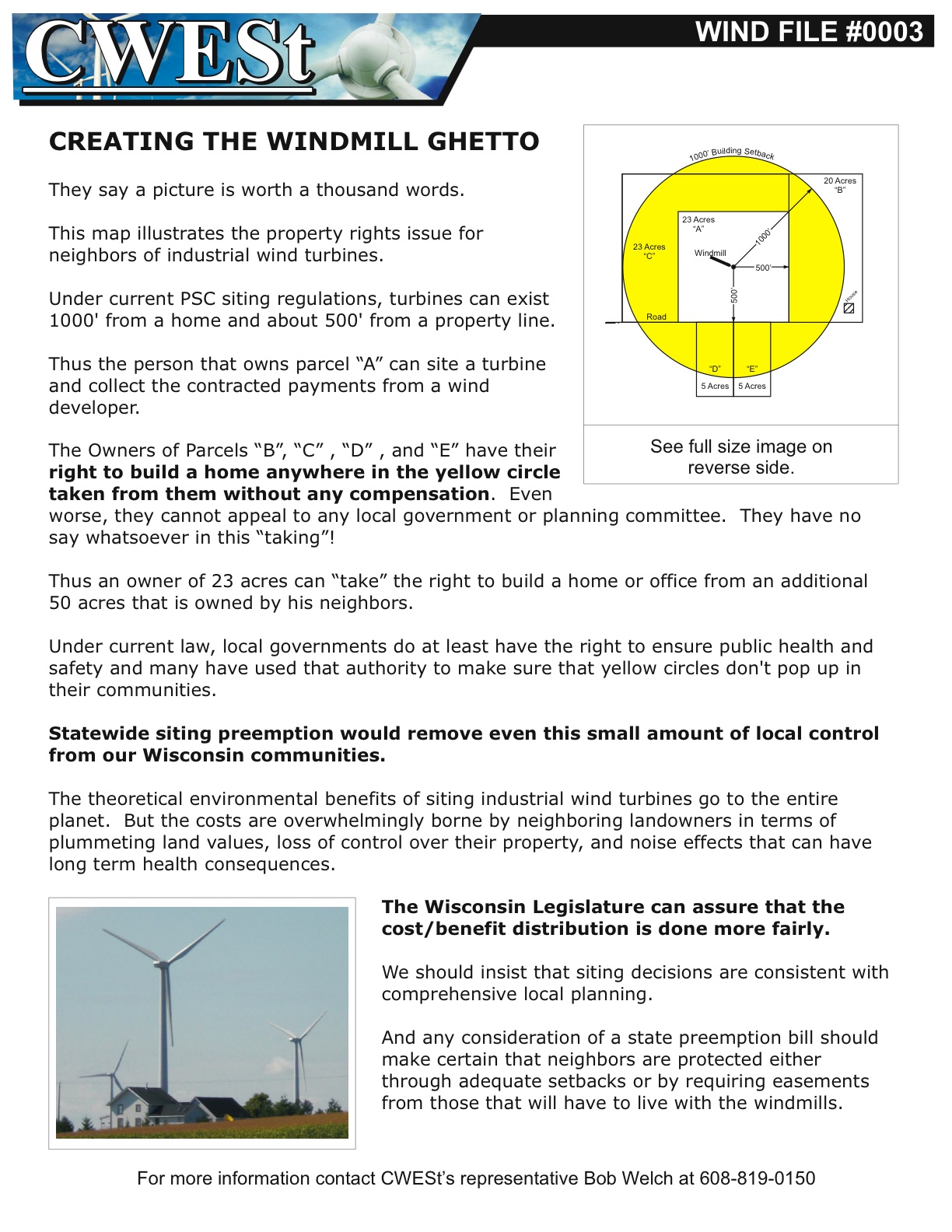

This graphic, adapted from one created by CWESt [down load it here] shows that when the 1250 foot setback is measured from a neighboring home, some of that neighbors land becomes a 'no-build' zone.

Once the turbine is up on your neighbor's land, you can't build on your own land if it is within 1250 of the turbine.

Under current PSC siting regulations, a 500 foot wind turbine on your neighbors property can be built as close as 1250’ from the foundation of your home.

Farmer A collects the contracted payments from a wind developer and farmers B,C,D,and E lose the right to build on their own land.

[The image above was adapted by Better Plan from this CWESt flyer.]

1/6/12 Giving the power back to local government: Wisconsin turbine siting issue takes a new turn

BILL ALLOWS COMMUNITIES MORE CONTROL OVER WIND TURBINE SETBACKS

By Trent Artus,

January 5 2012

Rick Stadelman, Executive Director of Wisconsin Towns Association said: “Local governments are responsible for protecting the public health and welfare of their communities. Arbitrary state standards limiting setbacks and noise levels of wind turbines take away the authority of local officials to protect their community. One size does not fit all. This bill allows local officials to exercise local control to protect the interest of their community.”

Madison, WI – State Senator Frank Lasee (R) of De Pere, WI introduced a bill allowing local communities to create their own minimum setback requirements for wind turbines. Current law doesn’t allow local communities to establish distances from property or homes that 500 feet tall wind turbines can be located.

[download copy of the bill by clicking here]

“Local communities should be able to create their own rules for public safety,” Lasee said. “We shouldn’t leave it to bureaucrats in Madison to make these decisions that affect home values and people’s lives. Madisonites aren’t the ones living next to the turbines. Having a statewide standard for the setback of these 500 feet tall wind turbines doesn’t take into account the local landscape. Local elected officials are most familiar with their area to set the correct setback distances and best represent their local constituents.”

“Over the last several months, I have spoken with numerous Wisconsin residents who have complained about wind turbines,” Lasee added. “These complaints range from constant nausea, sleep loss, headaches, dizziness and vertigo. Some have said the value of their properties has dropped on account of the turbines.”

Representative Murtha (R) of Baldwin, WI adds: “There have been many concerns raised about wind farms all over the state of Wisconsin. This bill will finally give local communities the control they have been asking for when it comes to deciding what is right for their communities and families.”

Officials and spokespersons for local communities and organizations support Senator Lasee’s bill.

Rick Stadelman, Executive Director of Wisconsin Towns Association said: “Local governments are responsible for protecting the public health and welfare of their communities. Arbitrary state standards limiting setbacks and noise levels of wind turbines take away the authority of local officials to protect their community. One size does not fit all. This bill allows local officials to exercise local control to protect the interest of their community.”

Steve Deslauriers, spokesman for Wisconsin Citizens Coalition said: “In order for wind development to be good for Wisconsin, it must be done responsibly and not in a fashion that sacrifices the health of those families forced to live within these wind generation facilities. Good environmental policy starts with safeguarding Wisconsin residents and we thank Senator Lasee for submitting this bill.”

“Wind turbine siting must be done at the local level as the population varies greatly, county by county, township to township. It is our goal to protect families within our township. This bill gives us the authority to do that.” Tom Kruse, chairman of West Kewaunee Township said.

Dave Hartke, chairman of Carlton Township added: “Carlton Township supports LRB-2700 because it places the authority for wind turbine siting at the local level where it belongs. As town chairman, I am always concerned for the health and safety of our residents.”

“We applaud Senator Lasee for introducing this bill.” Erv Selk, representative of Coalition for Wisconsin Environmental Stewardship said. “We have long thought that the Public Service Commission setbacks were not adequate to protect the people that live near the Industrial Wind Turbines.”

Senator Lasee said, “It’s about time we as legislators return local control over this important issue to the elected officials that know their area best instead of un-elected bureaucrats in Madison.”

Second Feature

BILL GIVES LOCAL CONTROL FOR DETERMINING WIND TURBINE RULES

Via Wisconsin Ag Connection, www.wisconsinagconnection.com

January 6, 2012

A Wisconsin lawmaker is introducing legislation that allows local communities to create their own minimum setback requirements for wind turbines. According to Sen. Frank Lasee, current law doesn’t allow local officials to establish distances from property or homes that 500 feet tall wind turbines can be located.

“Local communities should be able to create their own rules for public safety,” Lasee said. “We shouldn’t leave it to bureaucrats in Madison to make these decisions that affect home values and people’s lives. Madisonites aren’t the ones living next to the turbines.”

The De Pere Republican says having a statewide standard for wind turbine setbacks does not take into account the local landscape. He says local people are most familiar with their own area to set the correct distances and best represent their local constituents.

“Over the last several months, I have spoken with numerous Wisconsin residents who have complained about wind turbines,” Lasee points out. “These complaints range from constant nausea, sleep loss, headaches, dizziness and vertigo. Some have said the value of their properties has dropped on account of the turbines.”

Meanwhile, Wisconsin Towns Association Director Rick Stadelman support the effort. He says local governments are responsible for protecting the public health and welfare of their communities, and says arbitrary state standards limiting setbacks and noise levels of wind turbines take away the authority of local officials to protect their community.

The bill comes nearly a year after a joint legislative panel voted to suspend the wind siting rule promulgated by the Public Service Commission in December 2010. Those policies would have put into place standard rules that all areas of the state would need to follow when determining regulations for wind turbines.

1/4/12 What made this wind booster finally believe 'NIMBY' complaints have merit?

Video of a home in an Ontario wind project

WIND HISTORIAN AND BOOSTER URGES REMOTE LOCATIONS FOR NEW WIND TURBINES

Book review by Jim Cummings, Acoustic Ecology Institute

January 2, 2011

On the question of noise, Righter is equally sensitive and adamant, stressing the need to set noise standards based on quiet night time conditions, “for a wind turbine should not be allowed to invade a home and rob residents of their peace of mind.”

He says, “When I first started studying the NIMBY response to turbines I was convinced that viewshed issues were at the heart of people’s response. Now I realize that the noise effects are more significant, particularly because residents to not anticipate such strong reactions until the turbines are up and running – by which time, of course, it is almost impossible to perform meaningful mitigation.”

A new book, Windfall: Wind Energy in America Today, by historian Robert Righter, was recently published by University of Oklahoma Press. Righter also wrote an earlier history of wind energy, published by UofO Press in 1996. In the intervening years, of course, the wind industry has blossomed from its initial mini-boom-and-bust in the California hills (Altamont, anyone?), with bigger turbines, larger government incentives, and growing commitment to reducing our reliance on fossil fuels (coal and natural gas) for electric generation all leading Righter to feel that an update was in order.

As a hearty advocate of wind energy and continued rapid growth of the industry, Righter will startle many with his strong call for not building turbines “where they are not wanted.” He spends chunks of three chapters addressing the increasing problems caused by wind farm noise in rural communities, chides developers for not building farther from unwilling neighbors, and says that new development should be focused on the remote high plains, rather than more densely populated rural landscapes in the upper midwest and northeast. While not ruling out wind farms in the latter areas, he calls for far more sensitivity to the quality of life concerns of residents. (Ed. note: Righter’s book shares a title with, but should be clearly distinguished from, a recent documentary investigating local anti-wind backlash in a NY town.)

Righter seems to be especially sensitive to the fact that today’s turbines are huge mechanical intrusions on pastoral landscapes, a far cry from the windmills of earlier generations. At the same time, he suggests that a look back at earlier technological innovations (including transmission lines, oil pump jacks, and agricultural watering systems) suggests that most of us tend to become accustomed to new intrusions after a while, noting that outside of wilderness areas, “it is difficult to view a landscape devoid of a human imprint.”

He acknowledges the fact that impacts on a few can’t always outweigh the benefits for the many in generating electricity without burning carbon or generating nuclear waste, but goes on to ask:

No matter how admirable this is, should a few people pay the price for benefits to the many? Should rural regions lose the amenities and psychological comforts of living there to serve the city? Should metropolitan areas enjoy abundant electricity while rural people forfeit the very qualities that took them to the countryside in the first place? The macro-scale benefits of wind energy seldom impress local opponents, who have micro-scale concerns. The turbines’ benefits are hardly palpable to impacted residents, whereas the visual impact is a constant reminder of the loss of a cherished landscape.

Righter also takes a realistic stance about the fact that our appetite for electricity leads to inevitable conflicts wherever we might want to generate it. He says, “…wind turbines are ugly – but the public produced the problem and must now live with it. Turbine retribution is the price we must pay for a lavish electrical lifestyle.”

But unlike most wind boosters, he doesn’t content himself with this simple formulation. He goes on to stress that even as recently as 2000, most experts felt that technical hurdles would keep turbines from getting much bigger than they were then (500kW-1MW). The leaps that have taken place, with 3MW and larger turbines in new wind farms, startle even him: ”They do not impact a landscape as much as dominate it….Their size makes it practically impossible to suggest that wind turbines can blend technology with nature.” He joins one of his fellow participants in a cross-disciplinary symposium on NIMBY issues, stressing: ”Wind energy developers must realize the ‘important links among landscape, memory, and beauty in achieving a better quality of life.’ This concept is not always appreciated by wind developers, resulting in bitter feeling, often ultimately reaching the courts.”

He was obviously touched by the experience of Dale Rankin and several neighbors in Texas, who were affected by the 421-turbine Horse Hollow Wind Farm. Righter generally agrees with my experience there, that such wide open spaces seem the perfect place for generating lots of energy from the wind. But two of these hundreds of turbines changed Rankin’s life. These two sat between his house and some wooded hills, and Righter says that to him, “the turbines seemed inappropriate for this bucolic scene. For the Rankins the change is a sad story of landscape loss…” He asked whether the developer had talked with them before siting the turbines here, but they hadn’t, since the land belonged to a neighbor and local setback requirements were met, so “the utility company placed the turbines where its grid pattern determined they should be. Perhaps such a policy represents efficiency and good engineering, but (reflects) arrogance and poor public relations….(The developer) crushed Rankin with their lawyers when fairness and reason could have ameliorated the situation…the company could well have compromised on the siting of two turbines. But they did not.”

On the question of noise, Righter is equally sensitive and adamant, stressing the need to set noise standards based on quiet night time conditions, “for a wind turbine should not be allowed to invade a home and rob residents of their peace of mind.” He says, “When I first started studying the NIMBY response to turbines I was convinced that viewshed issues were at the heart of people’s response. Now i realize that the noise effects are more significant, particularly because residents to not anticipate such strong reactions until the turbines are up and running – by which time, of course, it is almost impossible to perform meaningful mitigation.”

While offering many nods to the constructive role of better public engagement early in the planning stages and making the case for societal needs sometimes outweighing those of a few neighbors, Righter also stresses:

While some objections to wind farms are clearly economically inspired and quite political in nature, no one can deny the legitimacy of many NIMBY responses. When the electrical power we want intrudes on the landscapes we love, there will be resistance, often passionate. This is part of the democratic process. The vocal minority, if indeed it is a minority, has a legitimate right to weigh the pros and cons of wind development in the crucible of public opinion, in public hearings, and if necessary in our court system.

As a bottom line, and despite his support for the industry and belief that we may learn to appreciate a landscape with more turbines, Righter calls strongly for new development to proceed in ways that minimize or eliminate intra-community conflict. Recounting one of many stories of a community torn apart by hard feelings between nearby neighbors (at the Maple Ridge Wind Farm in New York), he concludes:

Should the wind companies shoulder the blame? I believe they should. Good corporate citizens must identify potential problems and take action, and that action should precede final placement of the wind turbines….The most optimal ridge need not be developed at the expense of residents’ rights to the enjoyment of their property.

“In the final analysis,” writes Righter, “we can best address the NIMBY response by building wind turbines where they are wanted…and where they do not overlap with other land use options.” He elaborates:

Conversely, wind developers should give serious consideration to not insisting on raising turbines where they are not wanted…Unlike Europe, our nation has land. there are vast areas of the United States that have excellent wind resources and welcome the wind turbines….We can hope the industry will adopt the attitude of Bob Gates, a Clipper Wind Power vice president: “If people don’t want it, we’ll go someplace else.” Fortunately, the country can accommodate him.

Righter also stresses that current setbacks requirements encourage the building of wind farms in ways that almost inevitably cause heartbreaking problems for some neighbors. While at one point he makes the mistaken assumption that most setback limits are already a half mile or more, he addresses in some detail the findings of a 2007 report from the National Research Council’s Committee on Environmental Impacts of Wind Energy Projects. Righter observes that scientific difficulties with subjectivity led the committee to “shy away from the most important subject,” the impacts on humans, including social impacts on community cohesion and psychological responses to controversial projects. But he’s pleased to note:

Yet they did address one key impact on human beings: the fact that those individuals and families who suffer negative visual or noise effects from the turbines live too close to them. This is not the fault of the homeowners, for in most cases the home was erected before the wind turbines arrived. Usually it is attributable to local government regulations, which often allow setbacks of only 1,000 feet. Significantly, in their study the NRC’s wind committeee observed that ‘the most significant impacts are likely to occur within 3 miles of the project, with impacts possible from sensitive viewing areas up to 8 miles from projects.’

One might expect that this would preclude setbacks of less than at least a mile. But the industry prefers setbacks measured in feet rather than miles.

Righter’s book also includes chapters addressing grid integration, government incentives, reliability, and smaller turbines. He repeatedly makes the case for more research and development into smaller, vertical axis turbines, which, even with their smaller outputs, could be far more acceptable in many locations where landscape disruption and noise issues are paramount. Anti-wind campaigners won’t find Righter to be very comfortable company, for he sees the technological and grid challenges as easily surmountable, and the government support and investment in the industry as both warranted and of proper scale. He also supports various efforts to achieve better community consensus, including making royalty payments to those not hosting turbines. Make no mistake, this is an avid supporter of the industry.

Indeed, his long history and his deep knowledge of wind energy make his final recommendations about siting all the more striking. Righter’s experience and stance has fueled my confidence that the path AEI has been pointing to for the past year or so is more than the pipe dream of a tiny non-advocacy nonprofit. Larger setbacks, to protect unwilling neighbors from quality of life upheavals, combined with easements obtained via royalty-sharing or annual payments to neighbors who don’t mind hearing turbines a bit more often, is a fair and promising path forward.

As Righter says in his conclusion:

The days of an oil patch mentality of greed and boom-bust cycles are about over. Most developers understand that it is in their best interest to operate openly and in good faith with the local community. More problematical is the question of landscape. Wind turbines placed in a pleasing agrucultural, scenic, or historic landscape evoke anger and despair. At the heart of the issue is visual blight. Residents do not want to look at the turbines and are willing to fight wind development. Their wishes should be respected.

Wind developers should take to heart geographer Martin Pasqualetti’s advice: “If developers are to cultivate the promise of wind power, they should not intrude on favored (or even conspicuous) landscapes, regardless of the technical temptations these spots may offer.” The nation is large. Wind turbines do not have to go up where they are not wanted. We can expand the grid and put them where they are welcome.

NEXT FEATURE

From CNN

NEXT FEATURE

From The Waubra Foundation

From ABC

12/29/11 He's Baa-aaaak AND What wind turbine noise?

Bill Rakocy, Emerging Energies. Photo by Gerry Meyer, provided by Better Plan

Bill Rakocy, Emerging Energies. Photo by Gerry Meyer, provided by Better Plan

WIND FARM PLAN RETURNS

Via The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

By Thomas Content

A proposal to build a wind farm in western Wisconsin is back despite the opposition of local government officials, who rescinded permits for the project and adopted a moratorium on wind projects.

The proposal from Emerging Energies of Wisconsin was filed with the state Public Service Commission. It's the first proposal for a large wind farm filed with the state this year.

Hubertus-based Emerging Energies is seeking to build 41 turbines that would generate 102.5 megawatts of power in the Town of Forest in St. Croix County.

The state Public Service Commission has jurisdiction over large wind farms - any project with at least 100 megawatts - and will begin a review of the project.

A dispute over setbacks provided to wind energy projects has led to a stalemate for the wind industry on projects below 100 megawatts.

That stalemate resulted from protests over a statewide rule on wind siting developed last year by the PSC.

Wind opponents, including the Wisconsin Realtors Association, considered the proposal too restrictive on property rights. Last January, Gov. Scott Walker, who was backed by the Realtors in his election campaign against Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett, proposed a property rights bill that would require turbines to be located farther from nearby homes.

This fall, the governor's office and PSC expressed interest in a compromise between wind developers and property rights advocates.

"The PSC is still trying to facilitate a compromise," agency spokeswoman Kirsten Ruesch said.

No resolution is in sight, though.

Emerging Energies is trying to abide by standards set by the PSC when it approved We Energies' Glacier Hills Wind Park northeast of Madison, developer Bill Rakocy said. That wind farm began operation last week.

The setback standard requires that turbines be at least 1,250 feet from nearby homes. Unlike Glacier Hills, the Emerging Energies project would not require any waivers to exempt certain turbines from the setback requirement.

Rakocy said his wind project has been in development since 2007.

"We believe that, given the economy we find ourselves in, Wisconsin needs this project to move forward from an economic standpoint and a jobs standpoint," he said.

The developer is in talks with utilities that would buy the power, Rakocy said.

But local opposition to the project led to the formation of a citizens group, The Forest Voice, and subsequent recall of the entire three-member Forest Town Board earlier this year.

At that time, Emerging Energies was proposing to build four fewer turbines for a project that was under 100 megawatts.

The new town board voted at its first meeting in March to rescind building permits for the wind project and to impose a moratorium on wind power development.

Concerns about the project included the potential for having nearly 500-foot towers in the area.

As a result of the moratorium, the only way for Emerging Energies to build the project was to make it bigger. That triggers state agency review rather than local review.

The PSC has 360 days to rule on the project.

NOTE FROM THE BPWI RESEARCH NERD: The video below features residents of the same developer's first wind turbine project and what has happened to them since the turbines went on line.

At least two families have abandoned their homes in the eight turbine project because of turbine noise and pressure in the ears.

Emerging Energies has since sold the project.

Video courtesy of The Forest Voice-- visit their website by clicking HERE

"At least eight families living in the Shirley Wind Project in the Town of Glenmore just south of Green Bay, are reporting health problems and quality of life issues since the Shirley Wind project went online in December of 2010. Six families have come forward, five of them testify on the video, and at this time two of them have vacated their homes. STAND UP to protect people, livestock, pets, and wildlife against negligent and irresponsible placement of industrial wind turbines."

-The Forest Voice

The maddening sound people being asked to live with: Albany, NY --Wind turbine noise video via deepestdeepstblue

11/4/11 You break it, you pay: Lee County Illinois want's wind developers to give residents property value protection plan AND Same Turbines, Different Continent: the news from Down Under

MORE BACK PROTECTING HOME VALUES; PROPOSAL WOULD HELP THOSE NEAR WIND FARMS

BY DAVID GIULIANI,

SOURCE www.saukvalley.com

November 4, 2011

DIXON – A proposal to protect the property values of homes near wind turbines is gaining support.

Two of the five members of the Lee County Zoning Board of Appeals, which is reviewing the county’s wind energy ordinance, said at their meeting Thursday that they backed a home seller protection program for residents near turbines.

The discussion of the issue started with board Chairman Ron Conderman’s suggestion that the county not include such a program in its ordinance.

“Why add more burden to the county?” he asked.

Members Mike Pratt and Tom Fassler said they would like some version of the program, though.

“Ron, I disagree with you. I’m sorry,” Pratt said.

Two other members, Glen Bothe and Craig Buhrow, didn’t comment on the issue.

The board is basing its review on a proposed wind energy ordinance from Ogle County. That proposal calls for the home seller program to last 5 years after a wind project starts. Pratt pushed expanding that to 10 years.

Pratt wanted the program to affect homes within a mile of turbines, while Fassler suggested 1.5 miles.

The Ogle County proposal details a complex appraisal process, in which the homeowner and the wind energy company each choose an appraiser. In the end, if appraisers find that a home sold for less because it was near turbines, then the wind energy company would pay the difference.

County Assessor Wendy Ryerson has described the proposal as mostly workable, even though she said she hasn’t seen evidence that turbines cause property values to drop.

At Thursday’s meeting, Keith Bolin of Mainstream Renewable Power, which is planning a three-county wind farm, said he didn’t like the program because it would cause conflicts between wind farm companies and their neighbors.

Also, he said, any number of factors can cause a property value to drop, so it would be hard to attribute the decrease to a wind farm.

Franklin Grove Mayor Bob Logan said most wind companies were limited liability corporations. As such, he said, it was up to the county to limit residents’ liability. One way to do that was a home seller program, he said.

“Your obligation is not to help make wind companies get a profit,” he said.

Ryerson said she would bring some proposed language for the home seller protection program for the board’s next meeting on Nov. 17.

The board’s agenda for Thursday’s meeting included the issues of wind turbines’ noise, shadow flicker and the required distance between homes and wind turbines. But the board didn’t have time for those subjects.

The board has been meeting twice a month since the summer considering changes to the county’s ordinance. Its recommendations will be referred to the County Board, which has the final say.

To attend

The Lee County Zoning Board of Appeals meets at 7 p.m. Nov. 17 in the County Board meeting room, on the third floor of the Old County Courthouse, 112 E. Second St.

Go to www.countyoflee.org or call 815-288-3643 for more information.

NEXT STORY

Austrailia

WIND FARM SILENCE DEAFENING

Max Rheese, Weekly Times Now, www.weeklytimesnow.com.au 4 November 2011 ~~

Last week I received an email from a woman I had never met that almost brought me to tears.

It was a cry for help from someone crushed. She told a story of her family’s recent years of bewilderment, frustration, anger and despair.

Samantha Stepnell used to live with her husband and young son on their farm at Waubra, in western Victoria, 900m from the Waubra wind farm.

The family abandoned their home due to chronic sleep disorders experienced since the wind farm started operating.

Over an extended period of time, these sleep disorders degenerated into a range of deleterious health issues.

They have not sold their home; they have abandoned it.

They are not the only ones.

More than 20 homes have been abandoned in western Victoria because of Wind Turbine Syndrome.

Other families do not even have this option and are trapped by circumstances imposed upon them.

This pattern has manifested throughout the world in recent years since wind turbines have grown from the original 50m structures to 150m giants.

A study published last December by Danish researchers Moller and Pedersen linked bigger, modern turbines with increased noise impact.

These bigger turbines have been the preferred choice in Victorian wind farms.

No one claims everyone will get ill because of wind turbines.

Dr Daniel Shepherd and others have concluded from separate studies that 10-15 per cent of the population are more susceptible to noise than the general population.

From their experiences in Europe, multi-national wind energy companies operating in Australia have known since 2004 that health issues have been associated with wind farms – while asserting there are no peer-reviewed studies linking the two.

This was echoed last July by the National Health and Medical Research Council, which stated, “There is no published scientific evidence to positively link wind turbines with adverse health effects”.

It added: “While there is currently no evidence linking these phenomena with adverse health effects, the evidence is limited.”

Nine peer-reviewed studies have been published or approved for publication in science journals since July – and they link wind turbines with adverse health effects.

The recent Senate inquiry expressed clearly in its recommendations that the Federal Government study the health effects of wind turbines.

Since then the Victorian Government has amended planning legislation for new wind farms to require a 2km setback from residences, a 5km setback from 21 nominated regional towns and no-go zones in several regions of the state.

While this recognition of the problem is welcome, it does not address the turbines approved under old guidelines in the lead-up to the last state election.

When constructed, these new approvals will triple the number of turbines to affect 43 different communities in Victoria, with many of these turbines less than 2km from homes.

With the benefit of recent acoustical studies and medical papers, it has become increasingly clear there is a link between wind turbine operation and health effects, the only question is to what degree and what action to take.

The state has a duty of care to those who live in the communities earmarked for wind farms.

It is distressing that we can get public policy so wrong so much of the time and then take so long to fix it.

Max Rheese is executive director of the Australian Environment Foundation